Alden Albert Nowlan

Journalist, novelist, playwright, and—above all—poet, Alden A. Nowlan (25 January 1933 – 27 June 1983) was one of Canada’s leading literary figures. American poet Robert Bly, writing two decades after Nowlan’s death, rates the New Brunswicker as “the greatest Canadian poet of the twentieth century” (11). Nowlan’s legacy and influence stand with that of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman, whose graves lie close to Nowlan’s in Fredericton’s Forest Hill Cemetery.

Like the Confederation Poets, Nowlan, along with his contemporaries Al Purdy, Milton Acorn, Leonard Cohen, and Margaret Atwood, appeared at a time when a wave of Canadian nationalism led to widespread public support for Canadian culture. Nowlan, Purdy, and Acorn differentiated themselves from their modernist predecessors F.R. Scott, A.J.M. Smith, Irving Layton, Dorothy Livesay, and Earle Birney. While the modernists were mostly formally educated writers who remade mythology to embrace “the common man,” Nowlan, Purdy, and Acorn were themselves part of working class and unacademic Canada, and their poetry favours colloquial vitality over classical or scientific erudition. The trio’s eastern sensibilities, though, also differentiated them from their western counterparts of the Tish group such as Frank Davey, George Bowering, Daphne Marlatt, and Robert Kroetsch. While the Tish poets emulated the American Black Mountain Poets in their break with traditional poetic form in favour of the oral immediacy of performance, Nowlan, Purdy, and Acorn embraced popular history, poetic (as opposed to strictly literary) tradition, and engagement with the Canadian landscape.

The conversational and anecdotal style of Nowlan’s poetry, and his assertion that if “truck drivers read poetry, mine will be the poetry they’ll read” (Metcalf interview 16), might feed a misconception that his writing was unsophisticated. The discerning reader, however, will be rewarded with ample evidence that Nowlan explored and exploited poetic form. Grounded in the traditional end-stopped rhyme and ballad metre of his early lyrics, he soon expanded his poetic style to embrace a free-verse structure that employed irregular “breath unit” lines that showed his own debt to the Black Mountain Poets, although Nowlan was not interested in performing his poems at public readings. His true talent lay in his ability to juxtapose sentimentality and romanticism with irony and satire to create unforgettably honest, brutal, and touching portraits of the human heart.

For a writer who styled himself as working class, Nowlan in fact lived between the rural lumpen-proletarian and refined academic worlds, a close observer of both estates but a member of neither. His forebears immigrated to Nova Scotia from England and Ireland in the early-nineteenth-century, farming and cutting trees in the poorer regions of the Annapolis Valley. He was the first child of Grace (née Reese) and Freeman Nowlan, born in the village of Stanley when Freeman was 28 and Grace just 14 years old. Freeman was marginally employed as a seasonal worker, in winters as a pulp cutter and in summers as a mill hand in the neighbouring sawmill. Grace gave birth to Alden’s sister, Harriet, in November 1935.

Differences in Freeman’s and Grace’s age and temperament led to a breakdown in their marriage shortly after Harriet’s birth. Grace took the children and went to live with her mother in the adjoining village of Mosherville. When her mother died in 1940, Grace, confronted with the prospect of once again looking after her children full time, left them with Freeman, who in turn brought his mother into his home to help look after them. Alden rarely saw Grace after that and as an adult would claim that his mother was dead. His reintroduction to the Nowlan household coincided with the conversion of a small airstrip in Stanley to a full-fledged training base for pilots enlisting to serve in the Second World War. By all accounts Alden was a shy and awkward child at school; he would later claim, “The only thing I learned was how to do long division” (Cockburn interview 7). Although records do not show him as a registered student after Grade 4, he claims that he finally quit school 37 days into Grade 5. But he was by no means illiterate; in fact, his obsessive devotion to reading reinforced his solitary habits, both of which were sustained by his doting grandmother, Emma.

Emma’s indulgence and Freeman’s neglect contributed to Alden’s unhealthy retreat to his bedroom and his rich inner imaginative world. His condition and that of Emma began to worsen: she because of stomach cancer and he because of a wasting malady that the Reese relatives diagnosed as anaemia. In the spring of 1947, under threat from the Reeses to report him to the child welfare authorities, Freeman at last committed his son and his protesting mother to the care of Windsor’s Payzant Hospital, where Emma expired in July of that year. Although Alden regained his physical health, he remained inconsolable at the loss of Emma, and in the end child welfare workers did intervene and sent the young teenager to the Nova Scotia Hospital, a psychiatric facility in Dartmouth, NS. Soon after his fifteenth birthday, Alden was released from the hospital and put back into the care of Freeman, who pressed his son into service as his assistant cutting pulp in the woods around Stanley. Before long Alden was made night watchman at the mill, a job that gave him the chance to read during the long, uneventful nights. Convinced that editors would accept only typewritten manuscripts, his wages went towards the purchase of a mail-order typewriter, which took him three days to learn to use.

Determined to escape his village through writing, Alden penned occasional letters to radical socialist and workers’ newspapers along with contributing articles for the weekly Windsor Tribune. He received news of his first published poem (under the pen-name Max Philip Ireland) shortly before taking part in a government-sponsored rural folk school as a means of self-improvement and further socialization. When he was told about a reporting job at a weekly newspaper in Hartland, New Brunswick, Alden wrote his phoney resume (in which he gave himself a high school education and one year of newspaper experience) on Windsor Tribune stationery. The ruse worked, and on 18 March 1952, he left his native province for good.

In Hartland, Nowlan found employment, acceptance into a community, and a real possibility of developing himself as an artist. His status as an Observer reporter gave him entry into many of Hartland’s social activities, from town council politics to local sports organizations to community service clubs. One of his notable pals was Hartland native Richard Hatfield, who would become a supporter of Nowlan and, in 1970, the province’s premier. Nowlan’s efforts to get his poems published in little poetry magazines put him in touch with Fred Cogswell, poet and editor of the University of New Brunswick’s literary journal, The Fiddlehead. Surprised to find a notable Canadian poet and a literary magazine just a short drive from Hartland, Nowlan became a regular contributor to The Fiddlehead. In 1958 Cogswell published Nowlan’s first collection, The Rose and the Puritan, as a Fiddlehead Poetry Book.

Emboldened by his poetic success, Nowlan won a Canada Council Junior Grant of $2300 in 1961 to write his novel The Wanton Troopers, which would not be published until 1988, five years after his death. He obtained temporary leave from the Observer to complete the novel, and he wrote other works of short fiction during that time. Although Ryerson Press published his fourth poetry collection, Under the Ice, in 1961, neither Ryerson nor McClelland & Stewart was interested in The Wanton Troopers, which Nowlan eventually abandoned. After his fiction-writing sabbatical, Nowlan returned to the Observer with mixed feelings. The taste of artistic freedom afforded by the Canada Council grant made him feel more constricted by Hartland’s small-town environment. Not a safe driver at the best of times and cursed with a succession of unreliable cars, he travelled little outside Carleton County. But his job at the newspaper did put him into contact with Claudine Orser, a divorcee who was a linotype operator. The two started dating, and Nowlan soon fell in love. He began to look for better-paid employment that would take him out of Hartland and provide a life for him, for the woman he wanted to marry, and for her nine-year-old son, John.

In the summer of 1963 he, Claudine, and John moved to Saint John, where Nowlan had found a job as a reporter for the Telegraph-Journal. He quickly rose to the position of provincial editor and then night news editor. His circle of literary companions, which already included novelist Raymond Fraser and poet Gregory Cook, expanded to embrace other young writers and faculty members at the new Saint John campus of the University of New Brunswick. In March 1966, the sore throat that he had been complaining of for weeks was diagnosed as cancer of the thyroid, and in early April he underwent a series of three operations, any one of which could have been fatal. The surgery removed the thyroid and other glands and left scars that he grew a beard to hide. The re-routing of major blood vessels in his neck swelled his neck and lower face, giving him a much older and heavier appearance. His convalescence took several weeks and had profound effects, weakening his constitution and making him fear that he would not live for long. The literary community rallied around him and secured for him a Guggenheim Fellowship, which gave him the means to continue full-time writing and even travel with his family to England and Ireland. The intense experiences of that time forged a new poetic awareness in Nowlan, and his next collection, Bread, Wine and Salt, published by Toronto publisher Clarke, Irwin, won the 1967 Governor-General’s Award.

As the spectre of imminent death faded, Nowlan looked ahead for a more secure future that would help him avoid full-time newspaper work once his award money ran out. From his hospital bed he lobbied Cogswell to be considered for UNB’s new writer-in-residence position, which he was offered in 1968. The university also gave him accommodations in a small house that the university had just purchased at the west edge of campus on Windsor Street. Although he would continue to write for the Telegraph-Journal and for other magazines and newspapers, his reliance on journalism ended. Once established in Fredericton, he associated himself with other UNB faculty members with a literary bent who called themselves the Ice House Gang after the stone hut next to the Old Arts Building where they regularly met to read each other’s writing. The principal members were Robert Cockburn, Robert Gibbs, William Bauer, and Kent Thompson, all UNB professors. One of their young protégés, the fiction writer David Adams Richards, also became a close friend of Nowlan’s along with other student poets such as Jim Stewart, Al Pittman, and Brian Bartlett. Supported by his now-regular publisher, Clarke, Irwin, Nowlan produced more poetry collections—The Mysterious Naked Man (1969) and Between Tears and Laughter (1971)—as well as a collection of short fiction (Miracle at Indian River [1968]) and Various Persons Named Kevin O’Brien (1973), another semi-autobiographical novel.

In Fredericton his literary projects diversified. With painter Tom Forrestall he produced a coffee-table book, Shaped by This Land. He collaborated with theatre director Walter Learning on the 1974 play Frankenstein, which would be followed in succeeding years by other plays for stage and for radio. He was also engaged occasionally to write copy for the provincial government, including speeches for his old friend Richard Hatfield. Not all of his collaborations were artistic. With St. Thomas University professor Leo Ferrari he founded The Flat Earth Society of Canada, and the two of them along with Ray Fraser drew national attention with their tongue-in-cheek claim that Jim Stewart, a descendant of Bonnie Prince Charlie, was the rightful heir to the British Throne.

The university, with some assistance from the provincial government, continued to maintain the poet after the first term of his writer-in-residency expired in 1971. News of the renewal was accompanied by UNB’s award of an honourary doctorate to its unofficial poet laureate. Dalhousie University awarded Nowlan an honourary degree in 1973, and throughout the 1970s the poet was kept busy with reading tours, travelling to western Canada in 1978 and 1982. But the late 1970s and early 1980s was also a period of growing loneliness for the poet as UNB’s group of young writers matured as artists and as people, moving away from Fredericton and into their own careers. The poetry of Nowlan’s later period reflects the feelings of abandonment and the philosophical outlook of an old man near death looking back on life, even though he was only in his late 40s.

As his maturing friends turned away from alcohol, Nowlan’s drinking became more solitary and less social. His doctor warned him to cut back or risk diabetes. Nowlan did, in fact, lose weight in 1982, but his smoking and drinking did not abate. That year was a significant one for him, with his poetry collection I Might Not Tell Everybody This (his first since 1977’s Smoked Glass), with his continuing success with plays, and with the recently negotiated purchase of his papers by the University of Calgary library. He and Claudine vacationed in Cuba and again in Ireland. But he received a shock in early 1983 when his long-time publisher, Clarke, Irwin, went into receivership. Nowlan’s excessive weight, his smoking, and his night-time drinking had for years depressed his breathing, making sleep fitful. One night in early June of that year he collapsed in the shower that he sometimes took to relieve his breathing difficulties. An ambulance was summoned, but Nowlan went into cardiac arrest, and the re-routed blood vessels in his neck made it difficult to revive him. He remained in a coma until he expired on 27 June.

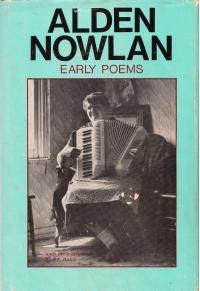

Nowlan’s first three collections of poetry, The Rose and the Puritan (1958), A Darkness in the Earth (1959), and Wind in a Rocky Country (1960), were 12- to 16-poem chapbooks that show a poet heavily influenced by Cogswell and—less directly—by American models such as Edgar Lee Masters in Spoon River Anthology. The chapbooks are distillations of some of Nowlan’s best poetry from the later phase of his “little magazine” career of the 1950s. Striving to write about the reality he knew, by the 1960s Nowlan claimed to have dropped his earlier attempts at what he later dismissed as “palpitating eternity poems” (“Something ” 10). But not all of his poetic output from the 1950s merits such dismissal, even from its author, for it points in the direction his later poems would follow: experimentation with both traditional and free verse, the development of dramatic voice, and the engagement with history and Christian myth.

The three Nowlan chapbooks that ushered him out of his little magazine phase contain short, lyric poems written mostly in regular rhyme and metre with end-stopped lines; in fact, the number of lines that begin with conjunctions such as “and” is noticeable, as in “The Brothers and the Village,” the opening poem of The Rose and the Puritan

For Jimmie whimpered when he saw a crow

Come down in answer to a classmate’s rock.

And fondled roses like a foolish girl,

And quoted school-book poets when he talked.And Tom shaped women with his pocket knife

From bits of wood, beneath a lazy tree,

Or frightened village maids with silly tales

About the beauty of love’s ecstasy. (5-12)

Here the and, for, and or contribute to the sense that the poet is creating a catalogue of the rural Maritimes, piling detail upon detail as he tours the reader through the lives of its inhabitants, a catalogue with entries such as “Warren Pryor,” “Aunt Jane,” and “Andy Shaw.” The details are not randomly chosen but rather invite the reader to see the irony of their juxtaposition. In the A Darkness in the Earth poem “In Awful Innocence,” the impersonal machine that is “[c]onvinced three cycles always meant a chair” (6) applies its dumb formula with tragic results: “inhale a child and twist its pretty neck, / [t]hen sprinkle varnish in its bloodied hair” (7-8). The juxtaposition Nowlan most wants the reader to see is that between the human and animal worlds, both when they collide and when they collude. Nowlan’s oft-quoted line from “A Night Hawk Fell with a Sound Like a Shudder”—“in any hunt I’m with the quarry” (5) —can be taken as a leitmotif for much of Nowlan’s early poetry, especially in his sensitive use of animal imagery to illuminate his themes of innocence and predation.

With his first full-length collection, Under the Ice (1961), Nowlan moves from the rural and animal world to explore the human community in the intensely social environment of the small town. This collection also marks the appearance of Nowlan’s first efforts at creating personal love poems, including the one Irving Layton found so touching, “Looking for Nancy,” in which the poet, after stopping various “girls in trenchcoats / and blue dresses” (3-4) in search of his beloved, concludes that his quest has been a “mistake” (13):

a broken streetlight,

too much rum or merely

my wanting too much

for it to be her. (14-17)

Although Under the Ice contains accomplished poems such as “Beginning,” “Christ,” and the underrated “These Are the Men Who Live by Killing Trees,” the collection suffers from the monotony of having similar poems grouped together, and the editors seem to have done little in the way of pruning the weaker poems to allow the stronger ones to stand out. All in all, Under the Ice has the flaws one might expect of Nowlan’s first full-length book by a national publisher: It attempts to introduce a new poet to a Canadian audience while offering less to the local audience who already knew and loved his poetry.

Canada’s literary critics of the early 1960s lauded this new backwoods bard, though Nowlan was to chafe at being pigeonholed as a merely regionalist writer. Critics from Atlantic Canada were most sympathetic to the validity of the material Nowlan was mining for poetic inspiration. Desmond Pacey in Creative Writing in Canada emphasizes Cogswell’s influence and Nowlan’s success at conveying “the mingled beauty and horror of rural New Brunswick with a straightforward honesty that shocks and grips the reader” (250). Less kind were some critics from Canada’s urban centres, as with Eli Mandel’s denial that “no one, surely, will mistake Nowlan’s Faulknerian world of barn-burning, bear-baiting, child whipping, and Saturday-night dances for the actual Maritimes” (91). Writing in the University of Toronto Quarterly poetry roundup for 1961, Milton Wilson predicted that “[i]f Mr. Nowlan ever really fulfils the potentiality of his early work, he should be a dominating (and maybe notorious) figure in Canadian letters of the next few decades” (444). The notoriety, though, lay in Nowlan’s stubborn resistance to the urbane and academic literary world that Wilson and other critics represented.

The collection that marked his physical departure from Hartland, The Things Which Are (1962), also marks Nowlan’s poetic departure from the rural portrait poems of Under the Ice. Though animal imagery still predominates in such poems as “Party at Bannon Brook,” “when the bobcat is not driven away / by smoke, and the eagle / makes reconnaissance from the coast” (27-29), here the poet feels more confident of his readers’ knowledge of history, especially its darker side represented by “Child Francis, Child Gilles” (4) descending the basement stairs in “The Genealogy of Morals,” learning that “[t]he same nightmares / instruct the evil, as inform the good” (7-8). The more intellectual stance in this collection is balanced by his engagement with Christian faith in such poems as “Christ” and “The Bull Moose” as well as a growth in the depth of his personal love lyrics in poems like “Canadian Love Song.”

His next two collections, 1967’s Governor-General’s-Award-winning Bread, Wine and Salt and The Mysterious Naked Man (1969), are composed of poems written mostly during his Saint John years, when his free verse form almost entirely dominates as his theme becomes intensely personal. “Daughter of Zion” from Bread, Wine and Salt reminds the reader of Nowlan’s earlier “village portrait” poems, but here the outside observer’s perspective is reversed, like the Holy Ghost who “went into her body and spoke through her mouth / the language they speak in heaven!” (25-26). Ecstasy, the sensation the poet experiences “look[ing] in at the world / like a ghost startled by the sight / of his own body” (“Five Days in Hospital,” 14-16, Nowlan’s emphasis) recurs in such poems as “I, Icarus,” one of many in which Nowlan returns to his Stanley childhood, this time as someone not removed in time but experiencing his past in the present. But personal exposure has its pitfalls, as with the character of the title poem of The Mysterious Naked Man, who has

… probably done

whatever it was he wanted to do

and wishes he could go to sleep

or die

or take to the air like Superman. (22-26)

Nowlan’s free verse line, sometimes long and sometimes short, is now governed by the breath unit, regulated by the conjunctions and, but, and or, which are posted at the entrance to many of his poems’ lines. These conjunctive sentries, however, sometimes cannot guard against masterful poems like “Ypres: 1915” from marching off in divergent directions. The Mysterious Naked Man marks a less-welcome new development: the Nowlan poem that is longer and more rambling rather than being narrative in its ambitions.

The best of Nowlan’s late-career verse in the collections Between Tears and Laughter (1971), I’m a Stranger Here Myself (1974), Smoked Glass (1977), and I Might Not Tell Everybody This (1982) are the poems that capitalize on his gift for capturing speech, either his own voice or the voices of various characters he creates. But economical and hard-hitting gems such as “The Red Wool Shirt” from Smoked Glass, where the female speaker concludes by saying, simply, “And that was that” (38), are balanced by less-disciplined dialogues such as “The Middle-Aged Man in the Supermarket.” Least successful of all are the Nowlan poems that are influenced by the reportage of Nowlan’s former journalism days.

But the tautness of Nowlan’s rare forays into longer narrative poems such as “On the Barrens” from Smoked Glass show Nowlan at his best when his characters do spread rumours about the pervasiveness of death. The poem that is considered to be his late masterpiece, “He Sits Down on the Floor of a School for the Retarded” from I Might Not Tell Everybody This, encapsulates both the self-insight and self-indulgence that respectively enrich and impoverish Nowlan’s poetry. Containing dramatic, narrative, and journalistic elements, the impact of this poem lies in watching it come close to losing its grip on its subject matter, wandering off on tangents that are later revealed to be germane with the secrets of the human heart. At many posthumous readings where Nowlan’s poetry has been celebrated, “He Sits Down . . .” is accorded the honour of being the last poem read.

Taken as a group, Nowlan’s works of fiction restrict themselves to usually bleak but occasionally redemptive sketches of single characters from rural villages or towns who contend with soul-destroying loneliness. In that his stories usually admit no more than one character and often just one scene in that character’s life is notable, these are truly short stories. However, stories such as “The Girl Who Went to Mexico” and “Will Ye Let the Mummers In?” demonstrate that he was capable of writing more than sketches, and he was able to follow more than one character and expand across more than one time period and setting.

Nowhere is Nowlan’s untapped gift for fiction writing more evident than in his two novels, Various Persons Named Kevin O’Brien (1973) and his posthumously published The Wanton Troopers. The convoluted publication history of the latter makes it difficult to situate the novels in chronological order. Although The Wanton Troopers was not published until 1988, it was the earlier of the two novels, and Nowlan’s superior handling of plot and character development gives it the feel of a novel written by a more mature writer. Various Persons is a postmodern novel without a postmodern artistic agenda. Its fragmented structure could be a result of Nowlan’s lack of confidence to tackle an extended work of fiction; instead, he creates a connective “meta-narrative” of the adult narrator’s return to his Nova Scotia home to string together a series of related short stories. Still, Various Persons is not a novel to be taken lightly. His tragic bildungsroman, The Wanton Troopers, relates a fictionalized version of the marital break-up of Judd (Freeman) and Mary (Grace) superimposed on young Kevin’s (Alden’s) struggle against the narrow mores of the village. The eleven-year-old narrator is torn between the sensuality of Mary and the Puritanism of Judd, a conflict exacerbated by his confused feelings towards his classmate, Nancy Harker. Mary’s flirtation with other men coincides with Kevin’s incipient sexual awareness, but when Nancy tries to seduce Kevin, he rejects her and, as his family disintegrates, he adopts a Biblical, creative imagination to defy the emotional pain he must endure.

While his fictional world is mostly restricted to tragic sketches of small people leading small lives, Nowlan’s dramatic oeuvre represents his imagination at its most expansive. His willingness to take imaginative forays outside his familiar literary landscape could well be due to the influence of his long-time collaborator, Walter Learning, the founding artistic director of Theatre New Brunswick. Nowlan, Learning, and TNB all arrived in Fredericton in the same year, 1968, and the Nowlans were regular theatregoers. In the theatre, Nowlan could allow himself to indulge in a love for melodrama, and he and Learning wrote the kind of popular successes that drew large audiences. All of their plays were historical pieces set in the nineteenth-century, and two in particular—Frankenstein (1974) and The Incredible Murder of Cardinal Tosca (1976)—call for elaborate period set pieces and costumes as well as spectacular theatrical effects.

Nowlan and Learning’s plays, though old-fashioned, were not (with the exception of Cardinal Tosca) melodramas in the strictest sense. Instead, their scripts subtly explore good and evil and how the two are intertwined. In a play such as The Dollar Woman (1977), this exploration takes the form of social debate between the characters. The dramatization of social issues in this play, along with the use of detailed stage directions, reminds readers of George Bernard Shaw. The playwrights do not make use of contemporary theatrical conventions such as character monologues, nor do they conceive of other audiovisual effects such as the projection of images. But the poem for voices that Nowlan wrote in 1970 without Learning’s collaboration, published as Gardens of the Wind in a 1982 limited edition, shows the direction Nowlan might have followed as a dramatist had he lived longer and been willing to experiment with the dramatic possibilities of unadorned voice.

Nowlan’s funeral reflected the community’s desire to memorialize their deceased literary lion. The unconventional ceremony in the tiny chapel at UNB was capped by a graveside service complete with bagpipers, Jim Stewart’s flute (played and then broken so that it would not sound another note), and friends and family sharing a cup of Irish whiskey before burying him shovelful by shovelful until the grave was filled. The many collections of his work published since his death attest to Nowlan’s continued popularity. Numerous selected editions of his poetry have appeared, most notably Robert Gibbs’s 1985 retrospective, An Exchange of Gifts; a selected poems for the US market, Thomas R. Smith’s What Happened When He Went to the Store for Bread (1993); and the Patrick Lane/Lorna Crozier selection titled Alden Nowlan: Selected Poems (1996). Interest in Nowlan continued into the twenty-first-century with two biographies, Patrick Toner’s If I Could Turn and Meet Myself (2000) and Gregory Cook’s One Heart, One Way (2002). The Writers’ Federation of New Brunswick hosted an annual Alden Nowlan Literary Festival from 2001 to 2004. The 2003 festival was held in the newly refurbished UNB Graduate Student Association office in Nowlan’s former residence at 676 Windsor Street. The office, along with its signature student bar, Windsor Castle Pub, has been lovingly restored with many interesting items of Nowlan memorabilia displayed on its walls. The recent publication of a selected edition of Nowlan poems by Bloodaxe Books in England attests to Nowlan’s continued popularity both at home and abroad and hints that his influence will continue into future years.

Patrick Toner, Fall 2010

University of New Brunswick

For more information on Alden Nowlan, please visit his entry at the New Brunswick Literature Curriculum in English.

Bibliography of Selected Primary Sources (Chronological)

Nowlan, Alden. The Rose and the Puritan. Fiddlehead Poetry Books 4. Fredericton, NB: Fiddlehead Poetry Books, 1958.

---. A Darkness in the Earth. Hearse Chapbooks 6. Eureka, CA: Hearse, [1959].

---. Wind in a Rocky Country. Toronto: Emblem, 1960.

---. Under the Ice. Toronto: Ryerson, 1961.

---. The Things Which Are. Toronto: Contact, 1962.

---. Bread, Wine and Salt. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1967.

---. Miracle at Indian River. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1968.

---. The Mysterious Naked Man. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1969.

---. Playing the Jesus Game. Trumansburg, NY: New Books, 1970.

---. “Alden Nowlan’s Canada.” Maclean’s June 1971: 16-17, 40.

---. Between Tears and Laughter. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1971.

---. “Hatfield Country.” Maclean’s Nov. 1971: 40-42, 76, 78, 80.

---. Various Persons Named Kevin O’Brien. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1973.

---. I’m a Stranger Here Myself. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1974.

---. Campobello: The Outer Island. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1975.

Nowlan, Alden and Walter Learning. Frankenstein: The Play. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1976.

Nowlan, Alden. “Something to Write About.” Canadian Literature 68-6 9 (1976): 7-12.

---. Smoked Glass. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1977.

---. Double Exposure. Fredericton, NB: Brunswick, 1978.

Nowlan, Alden and Walter Learning. The Incredible Murder of Cardinal Tosca. Fredericton, NB: Learning Productions, 1978.

Nowlan, Alden. “A Bubble Dancer and the Wickedest Man in Carleton County.” The Fiddlehead 125 (1980): 75-77.

---. “What About the Irvings?” Canadian Newspapers: The Inside Story. Ed. Walter Stewart. Edmonton, AB: Hurtig, 1980. 63-72.

Nowlan, Alden and Walter Learning. The Dollar Woman. New Canadian Drama 2. Ed. Patrick B. O`Neill. Ottawa, ON: Borealis, 1981. 111-53.

Nowlan, Alden. I Might Not Tell Everybody This. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1982.

---. Gardens of the Wind. Saskatoon, SK: Thistledown, 1982.

---. “By Celestial Omnibus to the Twilight Zone.” The Fiddlehead 136 (1983): 17-21.

---. Nine Micmac Legends. Hantsport, NS: Lancelot, 1983.

---. Will Ye Let the Mummers In? Toronto: Irwin, 1984.

---. An Exchange of Gifts. Ed. Robert Gibbs. Toronto: Irwin, 1985.

---. The Wanton Troopers. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane, 1988. Rpt. 2009.

---. What Happened When He Went to the Store for Bread. Ed. Thomas R. Smith. Afterword by Thomas R. Smith. 1993. Minneapolis, MN: Thousands Press, 2000.

---. Alden Nowlan: Selected Poems. Ed. Lorna Crozier and Patrick Lane. Toronto: Anansi, 1996.

---. White Madness. Ed. Robert Gibbs. Ottawa, ON: Oberon, 1996.

---. Road Dancers. Ed. Robert Gibbs. Ottawa, ON: Oberon, 1999.

---. Alden Nowlan and Illness. Ed. Shane Neilson. Victoria, BC: Frog Hollow, 2004.

---. Between Tears and Laughter: Selected Poems. Tarset, Northumberland, UK: Bloodaxe, 2004.

Bibliography of Selected Secondary Sources

Baxter, Marilyn. “Wholly Drunk or Wholly Sober?” Canadian Literature 68-69 (1976): 106-11.

Bieman, Elizabeth. “Wrestling With Nowlan’s Angel.” Canadian Poetry 2 (1978): 43-50.

Bly, Robert. “The Nourishing Voice of Alden Nowlan.” Preface. One Heart, One Way: Alden Nowlan: A Writer’s Life. By Gregory M. Cook. Lawrencetown Beach, NS: Pottersfield, 2003. 11-14.

Cameron, Silver Donald. “The Poet from Desolation Creek.” Saturday Night May 1973: 28-31.

Cockburn, Robert. Interview with Alden Nowlan. The Fiddlehead 81 (1969): 5-13.

Cogswell, Fred. “Alden Nowlan as Regional Atavist.” Studies in Canadian Literature 11.2 (1986): 206-25.

Cook, Gregory M., ed. Alden Nowlan: Essays on His Works. Toronto: Guernica, 2006.

---. “Amethyst Extra: Alden Nowlan.” Interview with Alden Nowlan. Amethyst 2.4 (1963): 15-25.

---. One Heart, One Way: Alden Nowlan: A Writer’s Life. Lawrencetown Beach, NS: Pottersfield, 2003.

Fraser, Keath. “Notes on Alden Nowlan.” Canadian Literature 45 (1970): 41-51.

Gibbs, Robert. “Various Persons Named Alden Nowlan.” The Alden Nowlan Papers. Comp. Jean M. Moore. Eds. Apollonia Steele and Jean F. Tener. U of Calgary P, 1992. xi-xxiv.

Mandel, Eli. “Turning New Leaves.” Canadian Forum July 1961: 90-91.

Metcalf, John. “Alden Nowlan.” Interview with Alden Nowlan. Canadian Literature 63 (1975): 8-17.

Milton, Paul. “The Psalmist and the Sawmill: Alden Nowlan’s Kevin O’Briens.” Children’s Voices in Atlantic Literature and Culture: Essays on Childhood. Ed. Hilary Thompson. Guelph, ON: Canadian Children’s Press, 1995. 60-67.

Oliver, Michael Brian. “Alden Nowlan and His Works.” Canadian Writers and Their Works. Ed. Robert Lecker, Jack David, and Ellen Quigley. Poetry Series 7. Toronto: ECW, 1990. 75-132.

---. “Dread of the Self: Escape and Reconciliation in the Poetry of Alden Nowlan.” Essays on Canadian Writing 5 (1976): 50-66.

---. Poet’s Progress: The Development of Alden Nowlan’s Poetry. Fredericton, NB: Fiddlehead Poetry Books, 1978.

---. “The Presence of Ice: The Early Poems of Alden Nowlan.” Studies in Canadian Literature 1 (1976): 210-22.

Pacey, Desmond. Creative Writing in Canada. Rev. ed. Toronto: Ryerson, 1961.

Toner, Patrick. If I Could Turn and Meet Myself: The Life of Alden Nowlan. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane, 2000.

Tremblay, Tony. “Alden Nowlan.” Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada. Ed. W.H. New. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2002. 835-37.

Tyrwhitt, Janice. “The Man from Desolation Creek.” Reader’s Digest Mar. 1984: 67-71.

Wilson, Milton. “Letters in Canada: 1961: Poetry.” University of Toronto Quarterly 31 (1961-62): 432-54.