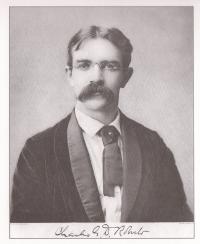

Charles G.D. Roberts

Photo: Sir Charles G.D. Roberts and the Tantramar, Charles Scobie

Known as the “father of Canadian literature” and unofficial leader of the Confederation Poets, Charles George Douglas Roberts (poet, pioneer of the animal story, editor, historian, Canadian nationalist) was born on 10 January 1860 in Douglas, New Brunswick, a small rural community 10 kilometres west of Fredericton. He was the first-born son of Reverend George Goodridge Roberts, an Anglican priest, and Emma Wetmore Bliss, whose father, the Honourable George Pidgeon Bliss, had served as Receiver General of New Brunswick.

Shortly after Roberts’ first birthday, his father was transferred to the parish of Westcock, near Sackville, where the family would remain for the next twelve years. Three years later, Roberts was joined by a sister Jane (b.1864) and, over the next ten years, three younger brothers: Goodridge Bliss (b.1870), Theodore (b.1877), and William Carman (b.1874). While in Westcock, Roberts was home schooled, mostly by his father, who was proficient in Greek, Latin and French; he also took painting lessons for a short time at Mount Allison University and at the Ladies’ College. At the age of twelve, he published his first writings: a series of three articles on farming in The Colonial Farmer.

In November 1873, Reverend Roberts was called back to Fredericton to assume duties as rector of Saint Ann’s Church. The next year Charles joined his cousin, Bliss Carman, at Collegiate School where the young men fell under the tutelage of Oxford educated George R. Parkin, who instilled in them a love of classics and English literature. In 1875, Roberts graduated from Collegiate as a gold medallist and that fall he began studies at the University of New Brunswick (UNB). He graduated in 1879 with a Bachelor of Arts with honours in mental and moral science and political economy.

Instead of following in the footsteps of his mentor and applying to Oxford, Roberts became principal of Chatham [New Brunswick] High School and Grammar School, a position he would hold for two years while completing his MA at UNB (1881). Two other events marked this period of his life: the first came in late December 1880 when he married Mary Fenety, a daughter of the Queen’s Printer for New Brunswick. The second event occurred in the spring of 1880 when he published his first collection of poetry, Orion, and Other Poems. Although it was very much an apprentice publication, the collection had energy and showed technical maturity; it also received favourable reviews in Canada and abroad, as well as encouraging personal notes from Matthew Arnold and Oliver Wendell Holmes to whom the brash young poet had sent copies. More importantly, the collection had a profound impact on Archibald Lampman, who credited Roberts for helping to inspire him to become a poet; Lampman remarked several years later that after being lent a copy he had “sat up most of the night reading and re-reading Orion in a state of the wildest excitement.”

In 1881, Roberts had had enough of Chatham and accepted the principalship at York Street School in Fredericton. But he did not stay long; in 1883 he went to Toronto to become the first editor for Goldwin Smith’s new magazine, The Week. The work proved to be an invaluable experience for Roberts; unfortunately, the hours were long and he and Smith became increasingly at odds over the question of Canadian independence. So, in the summer of 1884, Roberts returned to Fredericton. A year later he was appointed Professor of English, economics and French at King’s College in Windsor, Nova Scotia.

By the time Roberts was established at King’s, his family had grown to include two sons, Athelstan (b.1882) and Lloyd (b.1884), as well as a daughter, Edith (b.1886); Roberts’ youngest son, Douglas, was born in 1888. The demands of a growing family and full teaching load did not diminish his ability to write, though. On the contrary, the Windsor years proved to be a productive time for Roberts. During the late 1880s he wrote a regular review column for the Saint John Progress entitled “The World of Books.” He also published his second and third collections of poetry: In Divers Tones (1886) includes his important Romantic return poem, “The Tantramar Revisited,” while Songs of the Common Day (1893) demonstrates his increasing technical mastery over the sonnet form. In 1890, he produced an English translation of Aubert de Gaspé’s important early French-Canadian novel, Les Anciens Canadiens (1863) under the title, The Canadians of Old. He also published a travel guide, The Land of Evangeline and the Gateway Thither (1895).

His most significant publication during these years, though, was the short-story “Strayed,” which appeared in Harper’s Young People in 1889. Set in the backwoods and involving an ox and a bear, it was the first time animals had been depicted in fiction in their natural environment surviving according to their own instincts rather than being anthropomorphically portrayed as animals that simply mimicked human situations. This story marked the birth of the modern animal story and the beginning of Roberts’ prodigious output of such stories—he would go on to publish more than two dozen collections over the course of several decades.

Despite his literary achievements, as well as election to the Royal Society of Literature (1893), Roberts became increasingly frustrated by his isolation in Windsor and a lack of personal fulfilment as a college professor at a small university. In 1895, he resigned his position at King’s College and returned to Fredericton—a move that seemed to bolster his spirits as a writer, because the next year his creative output was prodigious. In 1896 he published his first novel, The Forge in the Forest, in which he channelled the historical energy of the Acadian Deportation; his fourth collection of poetry, The Book of the Native, which signalled a shift in his poetic oeuvre away from descriptive, technically tight Romantic verses to more mystical lyrics; his first book of nature-stories, Earth’s Enigmas, which included his earliest animal stories, a few supernatural narratives, and local colour pieces; and a book of adventure stories for boys, Around the Campfire.

By 1896 Roberts had achieved considerable success and fame in Canada. But the real creative centre of North America at the end of the nineteenth-century was New York. He departed in February 1897 alone and soon found work as an assistant editor for The Illustrated American. Unfortunately, tragedy struck at home: his first-born son, Althestan, died of typhoid fever on 16 October. His grief did not hinder his ambition though, and shortly after the funeral he returned to New York.

The following year he convinced his brothers Thede and Will to join him in New York. He helped Will find work with The Illustrated American while Thede landed a job at The Independent where Bliss Carman had worked as associate editor. For his part, Roberts resigned his position in order to focus his energies full-time on writing. In 1898, he produced a collection of love poems, New York Nocturnes, as well as his second Acadian novel, Sister to Evangeline (his last Acadian novel, Prisoner of Mademoiselle, appeared in 1904). Two years later, he published perhaps his best known and lasting novel, The Heart of the Ancient Wood, set in the New Brunswick backwoods. It involves a young woman named Miranda who has an uncanny ability to communicate with woodland creatures. This novel later inspired Marian Engels to write her own intimate narrative of nature, Bear, which won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction in 1976.

Although his Collected Poems appeared in 1901, followed by The Book of the Rose in 1903, the bulk of Roberts’ writings during the New York years were fiction. In 1902, he published Barbara Ladd, a much less polished work than The Heart of the Ancient Wood, but because it was set during the American Civil War it proved popular with readers, selling more than 80,000 copies. Due to the international success of fellow Canadian ex-pat Ernest Thompson Seton’s Wild Animals I Have Known in 1898, Roberts also had a ready audience for his own animal stories, and he began to produce stories for both North American and British magazines. Of particular note is The Kindred of the Wild (1902), his first full collection of animal stories, prefaced by an important critical essay from Roberts in which he defines the characteristics of the modern animal story. In fact, such was the popularity and controversy surrounding these kinds of stories that, in 1907, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, an avid outdoorsman, published an article in the June issue of Everybody’s Magazine accusing Roberts, Seton, William J. Long, and Jack London of being “nature fakirs” for what he saw as their less than accurate portrayal of animals.

In 1906, Roberts returned home to receive an Honorary LLD from UNB. That year he published his other celebrated novel, The Heart That Knows. Set in his childhood home of Westcock, the narrative involves another young protagonist, Luella Warden, who is abandoned by her sailor fiancé on her wedding day, and must raise her illegitimate son alone amid the daily judgements of a socially conservative town. Not surprisingly, the Anglican rector is a thinly disguised fictional model of his father, who had died the previous October. Restless for change, Roberts left for Europe in November 1907, and would not return to North America for eighteen years.

Accompanied by his son Douglas, Roberts’ journey began in France, and for the next three years father and son would divide their time between several French cities and parts of England. After Douglas returned home in 1910, Roberts spent time in Munich and Italy before settling in England in 1912. The next year he published his only popular thriller, A Balkan Prince, a narrative of international intrigue involving the dawn of air flight. The outbreak of World War I, however, stirred Roberts’ patriotism and at the age of 54 he joined the war effort, spending the first part of the war training officers before joining the Canadian War Records Office; he achieved the rank of Major by war’s end. He managed to publish one significant work during the war years: Lord Beaverbrook had commissioned a multi-volume set of histories that would record Canada’s role in the war, and in 1918 Roberts published Volume 3 of the series, Canada in Flanders. In 1919, he published New Poems, his first book of verse in sixteen years, as well as the strange pre-historic tale, In the Morning of Time. In June 1922 he received word that his childhood mentor, George Parkin, had died; four months later his sister, Jane, passed away and then, in February 1923, his mother died. In late 1924, family members proposed that Roberts return to Canada for a recital tour arranged by his sister-in-law. He agreed, and at the age of 65 he departed for Canada on 5 February 1925 after having lived away from his maternal home for nearly thirty years.

The cross-country tour was a success, and Roberts decided to stay in Canada, eventually settling in Toronto. The following year he received the first Lorne Pierce Medal, which the editor of Ryerson Press, Lorne Pierce, had established in order to recognize achievement in imaginative or critical Canadian literature. In 1927, he published a new book of poetry, Vagrant of Time; that same year he was elected National President of the Canadian Authors Association, and for the next two years would travel the country helping to organize and professionalize writers, as well as promote Canadian literature. In June 1929, his beloved cousin Bliss Carman died; the next year his estranged wife, May, passed away. Three years later, he published a new collection of animal stories, Eyes of the Wilderness; he also began editorial work on Volume I of the Canadian Who Was Who biography project sponsored by Trans-Canada Press. This was followed by two more collections of poetry: in 1934, he published his last major book, Iceberg, and Other Poems, a collection of modern lyrics; Selected Poems, chosen by Roberts, appeared two years later. On 3 June 1935, it was announced that Roberts would be knighted.

Near the end of his life Roberts finally produced creative work related to his war experiences. In 1941, he published a collection of poems, Canada Speaks of Britain, followed by his edited anthology, Flying Colours in 1942; that same year he was awarded an Honorary doctorate from Mount Allison University. On 28 October 1943, he married Joan Montgomery, with whom he had begun a relationship several years earlier when she assisted with Volume II of Canadian Who was Who. But their marriage was not meant to last: three weeks later, on 26 November 1943, Roberts died. The funeral took place in Toronto, but the following spring Lady Roberts brought his ashes to Fredericton, where he was interred in Forest Hill Cemetery, near his cousin Bliss Carman.

The end of the nineteenth-century was a golden age of literary culture for New Brunswick, and Roberts’ energy and celebration of the local landscape captured the spirit and essence of what literature in Canada would eventually become. More importantly, his prolific and diverse writings, invention of the modern animal story, and championing of biculturalism before the term even existed, made him a literary model against which all future New Brunswick writers would be judged.

In the time since Roberts’ death in 1943, two monuments have been erected in his memory: the first was a sculpture placed on the University of New Brunswick Fredericton campus in 1947 celebrating him, Carman, and their poet friend, Francis Sherman; the second monument, erected in 2005 in his childhood home of Westcock, was sponsored by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and signifies him as a person of national significance. Both monuments are well-deserved, for Charles G.D. Roberts did not become part of a literary tradition in New Brunswick: he and Bliss Carman began it.

Thomas Hodd, Summer 2011

Université de Moncton

For more information on Charles G.D. Roberts, please visit his entry at the New Brunswick Literature Curriculum in English.

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Aubert de Gaspé, Phillipe. The Canadians Of Old: An Historical Romance. Trans. Charles G.D. Roberts. Toronto: Hart, 1891.

Beaverbrook, Baron Max Aitken. Canada in Flanders. Vol. 1. The Story of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1916.

---. Canada in Flanders. Vol. 2. The Story of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1917.

Roberts, Charles G.D. Around the Campfire. Illus. Charles Copeland. Toronto: T.Y. Cromwell, 1896.

---. Autochthon. Windsor, NS: n.p., 1889.

---. The Backwoodsmen. New York, Macmillan, 1909.

---. Babes of the Wild. New York: Cassell, 1912.

---. A Balkan Prince. London: Everett, 1913.

---. Barbara Ladd. Illus. Frank Ver Beck. Boston: L.C. Page, 1902.

---. The Book of the Native. Boston: Lamson, Wolfe; Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1896.

---. The Book of the Rose. Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1903.

---. By the Marshes of Minas. Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1899.

---. Canada in Flanders. Vol 3. The Story of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. London; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1916.

---. Canada Speaks of Britain. Toronto: Ryerson, 1941.

---. The Canadian Guide-Book: The Tourist's and Sportsman's Guide to Eastern Canada and Newfoundland: Including Full Descriptions of Routes, Cities, Points of Interest, Summer Resorts, Fishing Places, etc. in Eastern Ontario, St. John County, the Maritime Provinces, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland: With an Appendix Giving Fish and Game Laws, and Official Lists of Trout and Salmon Rivers and Their Lessees. New York: D. Appleton, 1891.

---. Children of the Wild. Illus. Paul Bransom. New York: Macmillan, 1913.

---. Cock-Crow. New York: n.p., 1916.

---. The Collected Letters of Charles G.D. Roberts. Ed. Laurel Boone. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane Editions, 1989.

---. Discoveries and Explorations in the Century. London: W. & R. Chambers; Philadelphia: Bradley-Garretson Co., 1903.

---. Earth’s Enigmas: A Book of Animal and Nature Life. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Boston: L.C. Page, 1910.

---. Eyes of the Wilderness. Toronto: Macmillan, 1933.

---. The Feet of the Furtive. Illus. Paul Bransom. London: Ward, Lock, 1912.

---, ed. Flying Colours. Beverley House Library. Toronto, Ryerson, 1942.

---. The Forge in the Forest : Being the Narrative of the Acadian Ranger, Jean de Mer, Seigneur de Briart; and How He Crossed the Black Abbe; and of His Adventures in a Strange Fellowship. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1896.

---. Francis Sherman. Vol. 28. Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada 3. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada, 1934.

---. Further Animal Stories. London: J.M. & Sons, 1935.

---. The Haunter of the Pine Gloom. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Roberts' Animal Stories; Cosy Corner Series. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904.

---. The Haunters of Silence: A Book of Animal Life. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1907.

---. The Heart of the Ancient Wood. Boston: L. C. Page, 1900.

---. The Heart that Knows. Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1906.

---. A History of Canada. Boston: Lamson, Wolffe, 1897.

---. Hoof and Claw. Illus. Paul Bransom. London: Ward, Lock, 1913.

---. The House in the Water: A Book of Animal Stories. Illus, Charles Livingston Bull and Frank Vining Smith. Boston: L.C. Page, 1908.

---. The Iceberg and Other Poems. Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1934.

---. In the Deep of the Snow. Illus. Denman Fink. Toronto: Musson, 1907.

---. In Divers Tones. Montreal: D. Lothrop and Co., 1886.

---. In the Morning of Time. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1919.

---. Jim: The Story of a Backwoods Police Dog. New York: Macmillan, 1918.

---. The Kindred of the Wild. Boston: Page, 1902.

---. King of Beasts and Other Stories. Ed. Joseph Gold. Toronto: Ryerson, 1967.

---. The King of Mamozekel. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Roberts' Animal Stories; Cosy Corner Series. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904.

---. Kings in Exile. London: Ward, Lock, 1907.

---. The Land of Evangeline and the Gateways Thither. Kentville, NS: Dominion Atlantic Railway Co., 1890.

---. The Last Barrier and Other Stories. New Canadian Library 7. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1958.

---. Later Poems. Fredericton: C. Roberts, 1881.

---. Lines for an Omar Punch-Bowl: (to C.B.). New York: De Vinne Press, 1891.

---. The Little People of the Sycamore. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Roberts' Animal Stories; Cosy Corner Series. Boston: L.C. Page, 1906.

---. The Lord of the Air. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Roberts' Animal Stories. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904.

---. More Animal Stories. The King's Treasuries of Literature. London: J.M. Dent, 1922.

---. More Kindred of the Wild. London: Ward, Lock, 1910.

---. The Morning of the Silver Frost. New York: n.p., 1916.

---. Neighbours Unknown. Illus. Paul Bransom. London: Ward, Lock, 1910.

---. New Poems. London: Constable, 1919.

---. New York Nocturnes, and Other Poems. Boston: Lamson and Wolffe, 1898.

---. Orion, and Other Poems. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1880.

---, ed. Poems of Wild Life. The Canterbury Poets. London: W Scott.

---. The Prisoner of Mademoiselle, a Love Story. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904.

---. The Raid from Béausejour; and, How the Carter Boys Lifted the Mortgage: Two Stories of Acadie. Toronto: Musson, 1894.

---. Red Fox. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Scholastic Book Services Series T66. New York: Scholastic Book Services, 1905.

---. Red Oxen of Bonval. New York: Dood, Mead, 1908.

---. The Return to the Trails. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Roberts' Animal Stories; Cosy Corner Series. Boston: L.C. Page, 1905.

---. Reube Dare's Shad Boat: A Tale of the Tide Country. New York: Hunt & Eaton, 1895.

---. The Secret Trails. Illus. Paul Bransom and Warwick Reynolds. London: Ward, Lock, 1916.

---. The Selected Poems of Charles G.D. Roberts. Toronto: Ryerson, 1936.

---. The Selected Poems of Charles G.D. Roberts. Ed. Desmond Pacey. Ottawa: Tecumseh, 1955.

---. A Sister to Evangeline: Being a Story of Yvonne de Lamourie, and How She Went Into Exile With the Villagers of Grand Pré. Boston: Lamson and Co., 1898.

---. Some Animal Stories. London: J.M. Dent, 1921.

---. Songs of the Common Day and Ave!: An Ode for the Shelley Centenary. Toronto: W. Briggs; Montréal: C.W. Coates, 1893.

---. Spirit of Beauty. N.p.: n.p., 1930.

---. The Sweet o' the Year. Ryerson Poetry Chapbooks. Toronto: Ryerson.

---. They Who Walk in the Wilds. New York: Macmillan, 1924.

---. Thirteen Bears. Illus. John A Hall. Ed. Ethel Hume Bennett. Toronto: Ryerson, 1947.

---. Twilight Over Shaugamauk. Toronto, Ryerson, 1937.

---. Vagrants of the Barren and Other Stories of Charles G.D. Roberts. Ed. Martin Ware. Ottawa, Tecumseh, 1992.

---. The Watchers of the Trails: A Book of Animal Life. Illus. Charles Livingston Bull. Boston: L.C. Page, 1904.

---. Wisdom of the Wilderness. New York: Macmillan, 1923.

Roberts, Charles G.D. and Nathaniel A. Benson. "Reminiscences of Bliss Carman." Halifax: Dalhousie Review, 1930. 409-17.

Roberts, Charles G.D. and Arthur L. Tunnell, eds. A Standard Dictionary of Canadian Biography: The Canadian Who Was Who. 2 vols. Toronto: Trans-Canada Press, 1934–1938.

Roberts, William Carman, Theodore Roberts, and Elizabeth Roberts MacDonald. Northland Lyrics. Ed. Charles G.D. Roberts. Boston: Small, Maynard, 1899.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Adams, John Coldwell. Sir Charles God Damn: The Life of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1986.

Bentley, D.M.R. The Confederation Group of Poets, 1880–1897. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2004.

Cappon, James. Charles G.D. Roberts and the Influences of His Time. Toronto: W. Briggs, 1905.

Clever, Glenn, ed. The Sir Charles G.D. Roberts Symposium. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P, 1984.

Cogswell, Fred. Charles G.D. Roberts and His Works. Toronto: ECW Press, 1983.

Dunlap, Thomas R. “‘The Old Kinship of Earth’: Science, Man and Nature in the Animal Stories of Charles G.D. Roberts.” Journal of Canadian Studies 22 (1987): 104-20.

Early, L.R. “‘An Old World Radiance’: Roberts’ Orion and Other Poems.” Canadian Poetry: Studies, Documents, Reviews 8 (Spring/Summer 1981): 8-32.

Gold, Joseph. “The Precious Speck of Life.” Canadian Literature 26 (1965): 22-32.

Hodd, Thomas. “Charles G.D. Roberts’s Cosmic Animals: Aspects of ‘Mythticism’ in Earth’s Enigmas.” Other Selves: Animals in the Canadian Literary Imagination. Ed. Janice Fiamengo. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P, 2007. 184-205.

Lennox, John. “Roberts, Realism, and the Animal Story.” Journal of Canadian Fiction 2 (1973): 121-23.

MacLulich, T.D. “The Animal Story and the ‘Nature Faker’ Controversy.” Essays on Canadian Writing 33 (Fall 1986): 112-24.

MacMillan, Carrie, ed. The Proceedings of the Sir Charles G.D. Roberts Symposium. Sackville; Halifax: Centre for Canadian Studies, Mount Allison U and Nimbus Publishing, 1984.

Pacey, Desmond. “Sir Charles G.D. Roberts.” Ten Canadian Poets. Toronto: Ryerson, 1958. 34-58.

Pomeroy, Elsie. Sir Charles G.D. Roberts: A Biography. Toronto: Ryerson, 1943.

Roberts, Lloyd. The Book of Roberts. Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1923.

Ware, Tracy. “Remembering It All Well: ‘The Tantramar Revisited’.” Studies in Canadian Literature 8.2 (1983): 221-37.

Whalen, Terry. Charles G.D. Roberts and His Works. Toronto: ECW Press, 1989.