Martin Butler

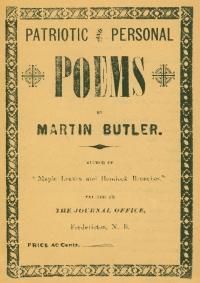

Martin Butler (1857–1915) was born on 1 September 1857 in the farming community of Norton, Kings County, New Brunswick. He was the last of eleven children (five surviving infancy) of an English emigrant mother and New Brunswick migrant father. The author of two collections of poetry—Maple Leaves and Hemlock Branches (1889) and Patriotic and Personal Poems (1898)—he edited and sometimes also printed and published his general interest, literary, and political newspaper, Butler’s Journal (1890–1915). Butler's Journal was a rurally-focused monthly, which featured poems (his own and others’), essays, opinion, humour, travelogues, local correspondence, original and reprinted political writings, letters, and miscellaneous literary expressions of woodsworkers, farmers and others of the rural working-class, as well as poetry and prose from New Brunswick, across North America, and occasionally England and Ireland.

As the titles of his two books of poetry suggest, Butler found dual inspirations in nature and the countryside, and in his and others’ rural and working-class experiences. The experiential and the political can be found, for example, in “Early Recollections,” a series of essays Butler published in the Journal in 1890–91 and which New Brunswick writer Bill Bauer realized the power and significance of in an early examination (1973). Both prose and poetry by Butler reveal a use of autobiography to illustrate both timeless themes and contemporaneous human dramas of the Second Industrial Revolution, as the latter affected even those “at the margins” of rural, pre-industrial society of New Brunswick.

Butler’s family, converted to Catholicism in the 1840s, lost their Kings County farm when a Saint John merchant foreclosed on a debt in the early 1860s. Butler’s childhood was consequently spent in lumber camps and marginal farmlands in Queens and Kent Counties, New Brunswick. His first education was received at home from his mother. When Butler was older, the family moved to a more settled farming area of York County, where he briefly attended school in exchange for the job of keeping up the fire in the schoolroom. He also worked as a farmhand for the Long family and began a longstanding friendship with a Long son, who later became a doctor, and whose early explorations of the natural world and of science inspired Butler. He was also briefly apprenticed to Kingsclear Baptist merchant and amateur poet and printer, George Hammond. Hammond’s influence can be seen in the anti-monarchical tradition Butler later emphasized in his journalism and poetry. These and other early educational and mentoring experiences were pivotal in introducing Butler to poetry, the art and craft of the printing press, and lifelong friendships and associations written about in his poetry and prose.

Hearing that jobs were to be had at the huge tanning factories being built in the woods of eastern Maine, in 1870–71 Butler’s family moved over the border to Grand Lake Stream, west of St. Stephen, New Brunswick. Butler again briefly attended school, including a boarding high school, but primarily worked alongside his father and one brother in the Grand Lake Stream and other nearby tanneries. It was in Maine that he began writing lively correspondence for newspapers such as the Fredericton Gleaner and the Calais Times. While in Maine, Butler was likely also exposed to American strains of radicalism and reform thought, but his later critique of industrial capitalism rests most vividly on an accident at the Grand Lake Stream tannery, which, in December 1876, took his right arm and nearly his life. He returned to New Brunswick after recovering from the amputation of his mangled arm. With the help of St. Croix Courier editor David Main, he began cobbling together a livelihood: of summers doing peddling, newsboy and related occupations in New Brunswick, and winters doing occasional barkmill work in the rural tanneries of Maine.

Butler also began writing poetry, and finding an audience for his poems among the farmers and other country people of New Brunswick. With the profits saved from peddling, factory work, and sales of Maple Leaves and Hemlock Branches, he was able to establish Butler’s Journal in Fredericton in 1890.

Butler looked after his aged mother from 1890 until her death in 1895, and shortly thereafter, he married Margaret McLean, a domestic who had been working in Kingsclear, New Brunswick. Margaret appears never to have been married before but census records and Butler’s private correspondence mention “Lily,” ten years old at the time of Butler and Margaret’s marriage, who was known by Frederictonians as Lily Butler. In 1897, Butler and Margaret had a son, Martin Albert, who was the source of much joy. Sadly, Lily barely survived young adulthood and Martin Albert died when only nine, in 1906. Shortly before his own death in 1915, Butler appears to have been caring in some capacity for Lily’s two children, his only grandchildren, while expressing dismay and disillusionment over the outbreak of World War I.

Butler’s body of work is quite limited; aside from Maple Leaves and Hemlock Branches, Butler’s Journal, and his other self-published collection, Patriotic and Personal Poems, he edited and published briefly only one other item, the more stridently anti-monarchical, anti-imperialist Canadian Democrat (1899–1902). It appears to have existed only as an insert in Butler’s Journal, but was a useful vehicle in advancing Butler’s anti-imperialist opposition to the South African (Boer) War, an unpopular position to take in imperialist Fredericton. That it was an insert in this paper during wartime, shielded the Journal from subscriber losses. Although the Canadian Democrat title—the paper given the same name as he gave his peddling cart in the 1880s—suggests an emphasis on Canadian nationalism, republicanism, and democracy, the appearance of the Canadian Democrat coincides with not only his opposition to Canada’s first imperial war, but also with the years of Butler’s intellectual exploration of the tenets of Christian socialism and his intense friendship with teacher, union organizer, and socialist Henry Harvey Stuart. A contemporary of the two Fredericton-born Confederation poets Bliss Carman and Charles G.D. Roberts, Butler seems only to have been acquainted with Roberts, a fact borne out by Roberts’ writing a sympathy note to Butler on the occasion of the death of Butler’s son.

Despite the limited scope and size of Butler’s published record, the force of Butler’s work is in his providing a voice to the often—though not always—voiceless. In this regard, his Maritime literary milieu contains the likes of New Brunswick’s Michael Whelan, a contemporary, and Cape Breton’s later labour poet Dawn Fraser, among many others who wrote “popular” verse or can be more closely aligned with the rich oral tradition of the region as a whole. Butler’ s eloquence, humour, witty political writings, and passion for wanting humans to work toward righting the world’s wrongs has resulted in his life and writings being fairly well known and insightfully used by labour and working-class historians. This historiography includes, most notably, David Frank’s early research and later Dictionary of Canadian Biography entry for Butler (1998) and Bryan Palmer’s mention in the seminal Working-Class Experience (1992). Butler’s contribution as a “brainworker” (Palmer 134-5) is associated with Butler’s and two other New Brunswickers’ establishment of the Fredericton Socialist League in 1902 (Frank and Reilly 1979). It is important to remember, however, that while his was a life of words it was also one containing a continuing familiarity with the labour and aesthetics of farm, mill, woods, and factory. Butler could, and did, in one column defend Walt Whitman as “one of the grandest souls of the 19th century” (May 1892), but also could, and did, a few issues later, report in his “Country Notes” column that it was “pig sticking season” (November 1892).

Butler identified himself as a poet, “peddler” (Butler, Maple Leaves and Hemlock Branches 8), editor, son, husband, parent, and workingman. In and through all of these roles, he was part of an expansive cultural and political network—from corresponding with Henry Harvey Stuart, Charles G.D. Roberts, and Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, to featuring the correspondence of countless New Brunswick mill workers and farmers in Butler’s Journal. While historically most literary journals were quite short-lived, Butler was able to keep his monthly light-hearted yet politically radical, literary but general interest, and rough but also respectable until just before his death—for an astounding twenty-five years. Part of this longevity is attributable to the custom of exchanges, wherein Butler sent copies of the Journal to other papers’ editors in exchange for copies of their publications, which Butler read and then shared with his readers. News, views, and arguments that percolated through the Journal included radical, reform, and, in the case of Georges-Isidore Barthe’s L’Indépendance canadienne, Canadian nationalist/independence/anti-imperialist and anti-monarchical ideas. Sexual liberty, freethinking, and state and anti-state forms of socialism were the result of exchanges with Montreal’s Patriot, Iowa’s Fair Play, and Boston’s (and Edward Bellamy’s) The New Nation. Connections to like-minded reform papers in the region included the Moncton Plain Dealer and Saint John Progress. Butler’s Journal even resurfaced in the 1970s by being reprinted in the briefly reincarnated Plain Dealer, a Fredericton-based, alternative newspaper.

Whether at home on the streets of Fredericton, or traveling and peddling during the summer months throughout New Brunswick and occasionally as far west as Quebec, Butler maintained long-running friendships and equally long-running subscriptions with farmers, mill workers, shopkeepers, and other rural dwellers in the countryside of New Brunswick. He was not averse to accepting vegetables, meat, and other foodstuffs in lieu of cash for a subscription. The June 1896 issue of Butler’s Journal also saw the Catholic Butler acknowledging, with thanks and a bit of his typical humour, a twelve-pound cake of maple sugar given him by a “Madawaska Protestant”! Lines from Butler’s opening poem in Maple Leaves and Hemlock Branches (the “Maple Leaf” representing, of course, New Brunswick, and “Hemlock Branches” representing the state of Maine) make explicit his relationship with those in southwestern New Brunswick:

When first I left the State of Maine,

The scene of so much toil and pain,

I found a home and liberty

In Charlotte, York and Sunbury.When wounded by misfortune's darts

Who was it took me to their hearts?

The stout and stalwart yeomanry

Of Charlotte, York and Sunbury. (1)

While the strength or merit of his verse and his skill as a poet may be called into question, Butler was without doubt taken “to [the] hearts” of the people in the New Brunswick countryside: people who proved to be his main support, and inspiration, for over thirty years. After a brief illness, Martin Butler refused surgery that might have prolonged his life and died in Fredericton on 24 August 1915.

Deborah Stiles, Fall 2010

Nova Scotia Agricultural College

For more information on Martin Butler, please visit his entry at the New Brunswick Literature Curriculum in English.

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Butler, Martin. Butler's Journal. Fredericton, NB: 1890 1915. [Incomplete] University of New Brunswick Library, Microfilm Collection Fredericton. There are two five year runs of Butler’s Journal, beginning with volume 1 issue 1: July 1890-June 1895, July 1898-June 1903. Issues of the Canadian Democrat can be found within the later run. This microfilm is also available at the MacRae Library, Nova Scotia Agricultural College. Researchers wishing to access additional non-microfilmed issues will find the following in New Brunswick: Butler’s Journal [one issue, March 1898] in York Sunbury Museum, MC 300 – York Sunbury Historical Society Archival Collection, Clippings (MS19 – 20 to 103), Item no. 38; and at UNB Library Special Collections (originals) the following issues: August 1895, October 1895, November 1895, January 1896, April 1896, June 1896, July 1896, August 1896, September 1896, December 1896, January 1897, February 1897, March 1897, April 1897, May 1897, June 1897, June 1898, February 1904, August 1904, September 1904, November 1904, February 1905, September 1905, December 1905.

---. Maple Leaves and Hemlock Branches. Fredericton, NB: Gleaner Job Office, 1889. [In Pre 1900 Canadiana Series, CIHM No. 00365.]

---. Patriotic and Personal Poems. Fredericton: The Journal Office, 1898. [In Pre 1900 Canadiana Series, CIHM No. 02844.]

Calais Times [Calais, Maine USA]. 16 November 1877 – 8 June 1883. Twenty-two correspondent’s reports, by Butler, published during this period.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Allaby, Gerald H. “New Brunswick Prophets of Radicalism: 1890–1914.” M.A. thesis. Fredericton: U of New Brunswick, 1972.

Bauer, William. Comp., Introd., “Martin Butler: Early Recollections.” The Journal of Canadian Fiction 2.3 (Summer 1973): 180 90.

Frank, David. “Martin Butler.” The Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 14. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1998. 164-6.

---. “The Several Lives of Martin Butler.” The Officers’ Quarters 20 (Spring and Summer 2003): 3-12.

Frank, David, and Nolan Reilly. “The Emergence of the Socialist Movement in the Maritimes, 1899–1916.” Underdevelopment and Social Movements in Atlantic Canada. Ed. Robert J. Brym and R. James Sacouman. Toronto: New Hogtown Press, 1979. 81-106.

Johnson, Daniel F. “Notes on Martin Butler.” The York Sunbury Museum. Daniel F. Johnson Newspaper Transcriptions. York Sunbury Museum, Fredericton, NB. 4 Sept. 2010.

<https://yorksunburymuseum.wordpress.com/2010/09/04/notes-on-martin-butler/>.

Palmer, Bryan D. Working-Class Experience: Re-Thinking the History of Canadian Labour, 1800–1991. 2nd ed. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1992. 132-5.

Stiles, Deborah. “Contexts and Identities: Martin Butler, Masculinity, Class, and Rural Identity, The Maine-New Brunswick Borderlands, 1857–1915.” Ph.D. diss. U of Maine, 1997.

---. “‘The Dragon of Imperialism’: Martin Butler, Butler’s Journal, the Canadian Democrat, and Anti-Imperialism, 1899–1902.” The Canadian Historical Review 85.3 (Sept. 2004): 481-505.

---. “The Gender and Class Dimensions of a Rural Childhood: Martin Butler in New Brunswick, 1857–1871.” Acadiensis XXXIII.1 (Fall 2003): 73-86. Rpt. Readings in Canadian Social History, Volume 1 – Pre Confederation. Ed. Jane Errington and Cynthia Commachio. Toronto: Nelson Education Ltd., 2006. 347-358.

---. “Martin Butler, Masculinity, and the North American Sole Leather Tanning Industry: 1871–1889.” Labour / Le Travail 42 (Fall 1998): 85-114.