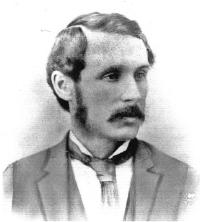

Sir George Robert Parkin

Photo: uoguelph.ca

Sir George Robert Parkin (educator, administrator, writer, imperialist) was born 8 February 1846 in Salisbury, New Brunswick, and died on 25 June 1922 in London, England. He was the son of John Parkin and Elizabeth (McLean) Parkin. His father was a Yorkshire farmer who immigrated in 1817; his mother was from Nova Scotia and of Loyalist descent. Parkin’s mother gave him a love for literature and learning that substituted for his occasional school attendance. He did, however, attend Normal School in Saint John in 1862, and then he taught briefly in Bouctouche and Campobello Island. He attended the University of New Brunswick in 1864, coming under the guidance of Anglican Bishop John Medley, whose library he admired and whose tutelage opened him to the wider world. After graduation, Parkin taught at the Bathurst Grammar School from 1867–1871. In 1873, he was appointed Headmaster of the Fredericton Collegiate School. He held that position until 1889, going down in New Brunswick literary history as the revered teacher of Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman (and for a brief time Francis Sherman).

On 9 July 1878, Parkin married Annie Connell Fisher, a former student who was twelve years his junior, and only nineteen when they were married by Bishop Medley in Fredericton. Annie’s grandfather was Peter Fisher, New Brunswick’s first historian. His Sketches of New Brunswick (1825) is considered the province’s first history.

After retiring from the Fredericton Collegiate School, Parkin went to England (alone) from 1889 to 1895. That would be the beginning of his disintegrating marriage. In England, he worked for the Imperial Federation League, which promoted the idea of a unified British commonwealth of former colonies. He travelled and gave lectures for the Imperial cause all across Britain and the world, exhausting himself in the process (Parkin, like his wife, suffered from nervous breakdowns his entire life). Seeking stability and calm for himself and his growing family, he came back to Canada. From 1895 to 1902, he was principal of Toronto’s Upper Canada College, in effect returning to the private boarding school model that he would champion as the educational ideal all his life. In June 1902, he left UCC and became an administrator of the Rhodes Scholarship Trust. He later claimed that his “whole life was a preparation for the work ... [of] the Rhodes Trustees,” writing, “The conception of Rhodes was on the direct line of the ideas about national unity which had filled my mind for many years, and it seemed to promise more than anything else the fulfillment of long cherished dreams” (qtd. in Willison 153). He retired in 1920.

According to Terry Cook, Parkin “was attracted to the idealism that animated much late 19th-century British and Canadian life” (DCB 1). He believed that a healthy and progressive community would result from the ethical character of citizens, and be moved with a sense of public service rather than a desire for material gain or individual glory (Cook DCB 1). Parkin put those ideals into his teaching, his speaking, and his writing. Imperial Federation: The Problem of National Unity (1892) was his principal manifesto. In the same year, he produced a school textbook, Round the Empire (1892), the objective of which was propagandistic. During that same year, while working for the London Times, he wrote a series of reports on Canadian history and geography, later published as The Great Dominion: Studies of Canada (1895). He also published the books Edward Thring, Headmaster of Uppingham School: Life, Diary and Letters (1898), Sir John A. Macdonald (1908), and The Rhodes Scholarships (1912).

During his year at Oxford (1873)—a year partly subsidized by Bishop Medley—Parkin met Edward Thring, Headmaster of Uppingham School. Thring’s ideas about public and secondary school education had a lifelong influence on Parkin, and laterally influenced the design of public education in New Brunswick and Ontario, where Parkin taught.

Parkin was a very significant and passionate man. Bliss Carman described him as a “sweeping and compelling personality that made him instantly the centre of any company, and his fluent conversation and ready laugh held his hearers. Serious world topics were always his chief interest, and on these he never tired of discoursing” (qtd. in Willison 254). Even though his idealism now seems dated and rather neo-colonial, his conservatism did instill “unity under the crown and service to nation before self” (Cook DCB 3), important values in their own right. His fear of “American economic integration and popular culture” reflected the larger fear of a neo-liberal “materialism and individualism” that would forsake “community and tradition” for individual advancement (Cook DCB 3).

Parkin’s grandson, George Parkin Grant, took up this fight in the pages of Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism (1965), where he speaks of the passing of his grandfather’s vision in the face of American dominance of Canadian culture. Grant’s rhetoric can still be heard in federal Conservative and New Democratic parties today (Cook DCB 3). In this way, one can sense the impact that George Parkin has had on social democracy in Canada. Though Parkin has become, in William Christian’s phrase, “Canada’s most famous forgotten man” (subtitle of biography), we are fortunate to have had him as an influential educator and champion of our Confederation poets.

Stacy McCarthy, et. al., Winter 2008

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Parkin, George. Edward Thring, Headmaster of Uppingham School: Life, Diary and Letters. 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1898.

---. The Geographical Unity of the British Empire. London: n.p., 1894.

---. The Great Dominion: Studies of Canada. London: Macmillan, 1895.

---. Imperial Federation: The Problem of National Unity. London: Macmillan, 1892.

---. The Rhodes Scholarships. Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1912.

---. Round the Empire. London: Cassell and Co., 1892.

---. Sir John A. Macdonald. The Makers of Canada. Toronto: Morang and Co., 1908.

Parkin, George R. Parkin Fonds. UNB Archives & Special Collections. 3 Apr. 2000. U of New Brunswick. 22 June 2020

<https://web.lib.unb.ca/archives/finding/parkin/parkin.html>.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Brown, R.C. “Goldwin Smith and Anti-Imperialism.” Imperial Relations in the Age of Laurier. Ed. C. Berger. Toronto: U Toronto P, 1969.

Christian, William. “Canada’s Fate: Principal Grant, Sir George Parkin and George Grant.” Journal of Canadian Studies 34.4 (1999): 88-104.

---. Parkin: Canada’s Most Famous Forgotten Man. Toronto: Blue Butterfly, 2008.

Cook, Terry. “The Canadian Conservative Tradition: An Historical Perspective.” Journal of Canadian Studies 8.4 (1973): 31-39.

---. “George R. Parkin and the Concept of Britannic Idealism.” Journal of Canadian Studies 10.3 (1975): 15-13.

---. “Parkin, Sir George Robert.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 15. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2005. Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. 2003. U of Toronto/U Laval. 22 June 2020

<http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/parkin_george_robert_15E.html>.

Elton, Godfrey. The First Fifty Years of the Rhodes Trust and the Rhodes Scholarships, 1903–1953. Oxford: Blackwell, 1955.

Grant, George Parkin. Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1965.

Mahon, Peter. “Parkin, Sir George Robert.” Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada. Ed. William H. New. Toronto: U Toronto P, 2002. 866.

Moore, Steve, and Debi Wells. Imperialism and the National Question in Canada. Toronto: S. Moore, 1975.

Roberts, Charles G.D. “Bliss Carman.” The Dalhousie Review 9 (1929–1930): 409-417.

Ross, Malcolm. “A Strange Aesthetic Ferment.” The Impossible Sum of Our Traditions: Reflections on Canadian Literature. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1986. 27-42.

Willison, John. Sir George Parkin: A Biography. London: Macmillan, 1929.