Mary Morris/Bradley

Mary (Coy) Morris/Bradley (shopkeeper, feminist, religious revivalist, author), was born in Grimross (Gagetown), New Brunswick, on 1 September 1771 to Edward J. Coy (formerly McCoy) and Amy Titus. She died on 12 March 1859. Bradley was first married on 15 February 1793 to David Morris. After their union, they lived in Maugerville Township, east of Fredericton. Several years later, in 1801, the pair settled into farming at Portland Point in the Saint John region, but in 1805, they were forced to give up the farm due to David’s poor health (Davies 209). The couple moved to the city of Saint John, where they kept a shop in their home until 1816, when David’s condition worsened (Carr-Fellows 52). Widowed in 1817, Bradley remarried in 1819 to Leveret Bradley and remained in the Saint John area for the remainder of her life (52).

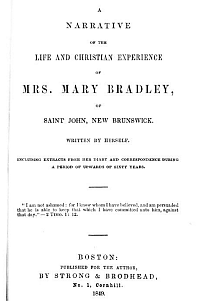

As the eighth of eleven children, Bradley only obtained a few months of formal education in her formative years. Nevertheless, she taught herself to write in order to record religious experiences in her diary (Dagg 46). Published in 1849 as her only work, the 375-page Narrative of the Life and Christian Experience of Mrs. Mary Bradley, of St. John, New Brunswick “endeavor[ed] to promote the glory of God and the good of fellow creatures” (Bradley 9). While the depictions of her conversion, spiritual experiences, and observations were typical of late-eighteenth-century religious journals, Bradley’s Narrative ultimately differs from others in that it offers insight into feminist history. Her journal depicts a frustrated woman restricted within her religion from an early age. This frustration was due to the fact that females were denied the right to preach or speak out during prayer.

Though lacking sophistication, Bradley’s diary is rich in feeling. Her disjointed autobiography depicts a woman with a strong social consciousness, so strong that it “created an evolving role for women” (Davies 206). Early in her Narrative, Bradley describes how she “experienced religion” at age sixteen (Bradley 76). During this “experience” she was “astonished beyond measure” by the impression that God was calling her to preach, yet like many other women who felt the call in the late eighteenth-century, she resisted (76). Her resistance arose from the fact that, having been raised a practicing Congregationalist, she had been indoctrinated in the church’s patriarchal structure, and thus felt unqualified to take a leading role in church ministry on account of her gender. Though a debate had emerged about female preachers in England and North America in the mid-eighteenth-century, the struggle for greater equality for women within the church was still in its infancy (Chadwick 25-9).

Though Bradley felt that God had “even for this cause ... raised thee up,” she recorded in her journal that she could not understand “how ... these things [could] be ...”:

A female to be called of God! ... I always heard that women had nothing to do in public respecting religious exercises, and that it was absolutely forbidden in the scriptures for a woman to pray in public, or to have anything to say in the church of God. (Bradley 46-7)

Bradley’s initial reluctance to speak publicly in church directly correlated to her role as a female in a religious society. However, she remained extremely frustrated by the constraints of social manners. She was well aware that her desire to preach went against convention, claiming “I knew that female exertions in a public way, were counted unscriptural ... I thought if I had been a man, nothing could hinder me from going abroad to proclaim salvation to a dying world” (Bradley 58, 150).

Though she initially resisted the call that she believed she had received from God in 1778, a visit five years later from a peripatetic Methodist missionary, Mr. Bishop, profoundly changed her life (Davies 207). In 1783, Bradley attended Bishop’s afternoon sermon and evening prayer meeting, wherein she first heard a women “lift up her voice to pray in public” (Davies 207). In the same meeting, Bradley again felt called “by a small still voice in [her] mind” to pray aloud. She did so “and was not disappointed” (207). From that time, she became enmeshed in a spiritual quest: both the struggle to give voice to her religious beliefs and ideas, and to do so within the restrictions of her society. She aligned herself with New Light Baptists and became interested in the religious movement known as the Great Awakening.

New Light Baptists and Congregationalists were, in essence, the same denomination, but the two groups took different positions regarding the Awakening. New Lights embraced the Awakening’s call for religious revival within all spheres of society, a notion that the Congregationalist Old Lights viewed with suspicion. However, Bradley was largely drawn to the New Lights because of another fundamental difference between the two religious factions: New Light spiritual leader Henry Alline’s emphasis on the importance of experiencing a powerful and emotional conversion (Rawlyk 24). Though leaders of the Great Awakening did not accept females preaching, the Church’s hierarchical and traditional authority was seriously weakened by the success that the New Light church had in redefining conversion as a strictly personal event, or as a direct receiving of the Holy Spirit (Bell 6). After being visited by the Holy Spirit, members naturally felt the desire to share their religious experiences, and they were encouraged to do so by the church. Moreover, New Lights allowed uneducated, unordained males to preach if called upon by God, which made it very difficult to exclude females who heard the same holy summons (Rawlyk 23).

As a woman who had always desired the right to publicly raise her voice in prayer, Bradley was naturally drawn to Alline’s religious theories. However, though she aligned herself with Alline and his New Lights movement in hopes of leading public worship and prayer, she was not allowed the space to do so within a Congregationalist setting. As before, she turned to her Bible for answers, and again “was not disappointed” (Davies 207; Bell 7). Bradley used her diary to reason her way through scripture-based opposition to female preaching—such as St. Paul’s admonition to silence—by determining that “though the apostle undoubtedly meant that [women] should not dictate or rule in the church, yet he could not have intended their exclusion from usefulness in the church, for in the apostolic age women prophesied” (Bradley 80). Her often-literary discussions with herself in the pages of her diary set the foundation for her emergence as the first female evangelist in the Maritime region.

Bradley remained a Congregationalist until approximately 1803 (Acheson 112). In that year, she insisted on the opportunity to speak publicly at church. When the Elders refused because she was a woman, she officially converted to Wesleyan Methodism in January. But before joining the Wesleyan church of Saint John, she and the church leaders held a meeting wherein both sides entered into a written agreement that “allo[wed] her all the liberties, and privileges, our heavenly father doth allow to the female sex, ... also, to improve her talents and bring her gifts into the sanctuary, as the Lord shall direct her, by his word, and Holy Spirit” (Bradley 160-1). This compact was a notable moment in the history of women’s rights. For the first time in the Maritime colonies, the church had granted a woman written consent to pray in public worship and to preach as she saw fit (Bell 8).

Remarkably, Bradley never recorded a single occasion of public prayer or exhortation—perhaps an indication of the difficulties she encountered, even after she secured the church’s consent to publicly pray and preach. The Wesleyan church continued to invite only men to pray at mixed sex meetings, though Bradley delighted in leading the all-female prayer group, “direct[ing], encourag[ing], and urg[ing] on [her] Christian sisters, in their heavenly journey” (Bradley 209-10).

Bradley was a remarkable woman whose diary provides rich historical insight into the difficulties that females faced in attempting to take on public roles in their communities. Her literary contribution to New Brunswick, while often overlooked, was also remarkable. Her diary was one of the two earliest books on religion and Christian beliefs written by women in Canada. “Published for the edification of readers and suitable for women authors who were writing from the private sphere,” her Narrative abounds with examples of the frustration she felt as an eighteenth-century woman attempting to alter the religious and social status quo of her era (Dagg 732). Though she did not become a preacher, her diary illustrates that women could effect change for themselves, since Bradley was able to carve out a small space for herself in the public sphere. Her diary is therefore significant in that it records the manner in which an obscure woman from a small Maritime colony redefined the role of women in the Methodist church. Bradley’s journal also reminds us that for every woman who made herself visible to history in some way, there were many more who heard God’s call and sought encouragement in Scripture, but who were held back by the constraints of their social circumstances.

Susan Shurtleff, Spring 2012

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Bradley, Mary [Coy]. Narrative of the Life and Christian Experience of Mrs. Mary Bradley, of St. John, New Brunswick, Written by Herself; Including Extracts From her Diary and Correspondence During a Period of Upwards of Sixty Years. Boston: Strong and Brodhead, 1849.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Acheson, T.W. “Methodism and the Problem of Methodist Identity in Nineteenth-Century New Brunswick.” The Contribution of Methodism to Atlantic Canada. Ed. Charles H.H. Scobie and John Webster Grant. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1992. 107-23.

Bell, D.G. “Allowed Irregularities: Women Preachers in the Early 19th-Century Maritimes.” Acadiensis 3.2 (2001): 3-39.

Carr-Fellows, Jo-Ann. “Mary Coy Bradley.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 1851–1860. Ed. Francis G. Halpenny and Jean Hamelin. Vol. 8. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1985.

Chadwick, Owen. “Methodist Origins in Britain and Atlantic Canada: John Wesley and the Origins of Methodism.” The Contribution of Methodism to Atlantic Canada. Ed. Charles H.H. Scobie and John Webster Grant. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1992. 11-31.

Dagg, Anne Innes, ed. The Feminine Gaze: A Canadian Compendium of Non-Fiction Women and Authors and Their Books, 1836–1945. Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier UP, 2001.

Davies, Gwendolyn. “In the Garden of Christ: Methodist Literary Women in Nineteenth-Century Maritime Canada.” The Contribution of Methodism to Atlantic Canada. Ed. Charles H.H. Scobie and John Webster Grant. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1992. 205-17.

Gerson, Carole. Canadian Women in Print, 1750–1918. Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier UP, 2010.

Rawlyk, G. Wrapped Up in God: A Study of Several Canadian Revivals and Revivalists. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1993.