Matthew Richey Knight

In Methodist Magazine, Vol. 34

Reverend Matthew Richey Knight was born 21 April 1854 in Halifax, Nova Scotia to Thomas Frederick Knight (1828–1902) and Mary Augusta Knight (1826–1916). He died on 27 January 1926 in Hants County, Nova Scotia.

A Methodist minister, Knight was the grandson of two renowned Methodist clergymen, Rev. Richard Knight, D.D. and Rev. Matthew Richey, D.D., as well as the nephew of Lieutenant Governor Matthew Richey of Nova Scotia. Knight was married twice, first to Louisa Beer in 1879 and then, after Beer’s premature death, to Alicia R. Weeks in 1888. Knight had four children between his two marriages (Goss 84).

Knight received primary and secondary education from schools in Dartmouth and Halifax and then obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from Mount Allison University in 1875. Always interested in writing, he played an essential role in the founding of Mount Allison’s student newspaper, The Argosy, and served as the first editor-in-chief (Handbook 73). Thankful for his time at Mount Allison, Knight dedicated several poems to the school. In “Ode to My Alma Mater,” he shares his love of place and states that the school will always be his home:

All hail! Ye dear familiar walls,

Where now strange forms and faces are.

Strange voices speak, strange figures move,

But do not change the halls I love.

My heart is with thee, happy place!

My memories of thee no future can efface! (Poems of Ten Years 106)

After teaching for two years at various public schools across the Maritimes, Knight began practicing Methodist ministry and was received as a probationer in Souris, Prince Edward Island (MacMurchy). He was ordained in Charlottetown in 1879 and later practiced in ministries throughout New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island (Goss 83). In his forty-six-year ministry career, he was a conscious and thoughtful minister, often delivering informative sermons that were especially sincere (Goss 84). As his influence increased, he went on to hold a series of positions in the ministry, such as chairman of the district, president of the conference, and a delegate to the general conference (Goss 84). Upon retiring in 1921, he was appointed as a superannuated minister, a clergyman without a congregation but still expected to partake in occasional pastoral duties when required (Goss 84; Patton, et al. 108).

Knight’s poetry – which appeared in various anthologies, journals, and magazines such as Harper’s Magazine; The Methodist Magazine Devoted to Religion, Literature, and Social Progress; Younger American Poets; New York Independent; and others – is deeply inspired by his faith and is unapologetically explicit in its dedication to Christianity. In the poem “Post Mortem,” he looks to divinity to answer his questions: “We seek the truth! O God reveal / the light so masked by cloud and mist!” (Poems of Ten Years 67). In this 1887 work, his only collection of poetry, Knight dedicates several poems to exploring the religious themes that preoccupied him. A few of his memorable and important poems are “Between Two Faiths,” “To Heaven Through Palestine,” and “Transmigration.” As part of the collection, he also translated traditional Italian sonnets and hymns, that interest in translation likely stemming from the influence of Mount Allison University professor of Classics, Alfred D. Smith, a favourite professor of Knight’s.

Despite being recognized for his “scholarly tastes and graceful verses,” Knight’s poetry was often viewed by critics as inadequate, unoriginal, and secondary to that of other Canadian and American poets (Hay). In that, his work, mused Douglas Sladen, did not contribute to Canada’s “day in poetry” that “has not yet come,” and was unable to compete with the poetry of Edgar Allen Poe or Ralph Waldo Emerson (li). New Brunswick poet and scholar Fred Cogswell took a different view, recognizing the foundational contributions of Knight’s poetry to the evolving Canadian canon. Cogswell was especially appreciative of Knight’s efforts to encapsulate the nostalgia of beginnings for early settlers in New Brunswick (108). Cogswell also observes, however, that Knight’s poetry ultimately fails to reveal anything individualistic and personal because, like his contemporaries, his “content was so subservient to form that the results all too often appear artificial and bookish” (Cogswell 108, 112). Although largely derivative and limited by formal constraint, Knight, concludes Cogswell, worked in the fashion of Matthew Arnold and Walter Savage Landor in turning his sonnets and epigrams toward a higher idealism (112).

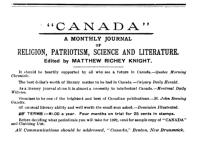

That idealism made Knight a fierce advocate for Canadian nationalism, evident in his founding and operating of various literary magazines in New Brunswick. The most successful of those, Canada: A Monthly Journal of Religion, Patriotism, Science, and Literature, was first published in January 1891 in Benton, New Brunswick, and ended in July 1892 in Hampton, New Brunswick. A longtime dream of Knight’s, Canada was comprised of poetry, histories, and translations, and featured contributions from well-known literary figures such as Archibald Lampman, Bliss Carman, and Charles G.D. Roberts. Knight’s intent was to “create, where it is uncreated, and to foster and develop, where it exists, a spirit of Christian patriotism in Canada” (“The Editor’s Portfolio” 8).

After Knight left Benton for Hampton, only one more edition of Canada was printed. The rapid emergence of literary magazines in Canada ultimately crowded the field to the extent that Canada ceased publication. In the last issue of Canada, Knight writes that “when Canada was started … there was no publication of the kind in the Dominion. We thought there was an open field… There may be room for all of these; we hope there is. The only hope of success, however, lies in each occupying a field and cultivating an individuality of its own” (“Editorial Notes” 152). In 1896, Knight would go on to publish a stamp-collection journal, Philatelic Messenger and Monthly Advisor, which circulated between Boiestown and St. Stephen, New Brunswick for five years (Folster). In 1901, pursuing similar publishing interests, Knight became the founder and editor-in-chief of the newspaper Boiestown Record, publishing a single issue on Christmas day. His publications, then, were enthusiastically conceived but short-lived.

Evident in his poetry and publications was the fact that Knight was an unreserved nationalist. He sought to unite the provinces of Canada and write with an influence that could be “felt from Atlantic to Pacific and would reach through eternity” (“The Editor’s Portfolio” 8). In his poetry, he celebrates the relationship between Great Britain and Canada, often referring to Great Britain as “mother,” but ultimately rejects imperial power, a view evident in the poem “Canada to England” (Poems of Ten Years 23). In a sonnet paying tribute to French explorer Jacques Cartier, he adopts the daring persona of the navigator, embracing Cartier’s “strong, dauntless soul” as “ours to claim” for Canada (“Jacques Cartier,” Poems of Ten Years 103). As “nation-builders,” he asserts in the poem “A Welcome,” we must create a national identity independent from the “motherland” (Poems of Ten Years 27).

In the years leading up to his death, Knight was confined to his home in Hants County, Nova Scotia due to limited mobility. He died there on 27 January 1926 without severe illness, ready to meet the divine creator:

Then bow thy spirit to His beck;

What He appoints is right.

His yoke is for the willing neck –

The load of love is light. (“Rest,” Poems of Ten Years 97)

Jamie Foster, Winter 2020

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Knight, Matthew Richey. “Editorial Notes.” Canada 2.7-8 (Jul./Aug. 1892): 143-154.

---. “The Editor’s Portfolio.” Canada 1.1 (Jan. 1891): 1-10.

---. Poems of Ten Years, 1877–1886. Halifax: MacGregor & Knight, 1887.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Cogswell, Fred. “English Poetry in New Brunswick Before 1880.” A Literary and Linguistic History of New Brunswick. Ed. Reavley Gair, et al. Fredericton: Fiddlehead Poetry Books & Goose Lane Editions, 1985. 107-116.

Folster, David. “N.B.’s Big Stamp Controversy: He Replaced Queen With Himself.” Telegraph-Journal [Saint John] 30 June 1984: n. pag.

Goss, Warren W. Methodists, Bible Christians and Presbyterians in Prince Edward Island: Campbellton – Miminegash. St. Lawrence: Campbellton-Miminegash Fellowship Group, 1984.

Handbook of the Institution of Mount Allison: The Central Institutions of the Maritime Provinces Containing Information for the Benefit of Intending Students. Sackville: Eurhetorian Society of Mount Allison U, 1903.

Hay, G.U. “Current Periodicals.” The Educational Review (Jan. 1891): 129-130.

MacMurchy, Archibald. Handbook of Canadian Literature. Toronto: William Briggs, 1906.

Patton, James, et al., eds. The Canada Law Journal, Volume XXIII. Toronto: Canada Law Journal Office, 1887.

Roberts, Charles G.D. The Canadian Guide-Book, Complete in One Volume. Montreal: Montreal News Co., 1899.

Sladen, Douglas, ed. Younger American Poets: 1830–1890. New York: Cassell Publishing Co., 1891.

Withrow, W.H., ed. The Methodist Magazine Devoted to Religion, Literature, and Social Progress. Toronto: William Briggs, Methodist Publishing House, 1890.