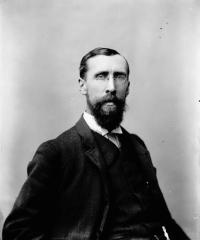

Sir George E. Foster

Photo: Libraries and Archives Canada

Sir George Eulas Foster (politician, lecturer, and teacher) served in the cabinets of no fewer than seven Conservative prime ministers and had an often overlooked but influential political career spanning more than fifty years. He was born on 3 September 1847 on the banks of the St. John River in Wakefield, Carleton County, New Brunswick, and died at his home in Ottawa, Ontario, on 30 December 1931. His mother, Margaret Foster (Heine) died when Foster was three years old; he was raised by his father, John Foster, a farmer and second-generation United Empire Loyalist who lived his whole life in Wakefield. In 1889 Foster married Adeline Chisholm (Davies), one of the founders of the temperance movement in Ontario and the former wife of disgraced MP Daniel Black Chisholm. Following her death on 17 September 1919, Foster was remarried to Jessie Allan, daughter of British MP Sir William Allan.

Foster was the youngest of seven children and grew up in relatively poor surroundings with little formal education. Having no school in his settlement, he was forced to board out or walk the many miles to a neighbouring settlement. His father only owned one book, the Bible, and Foster would supplement his appetite for reading by borrowing books from his neighbours–the most influential being Milton’s Paradise Lost and The Works of Josephus.

At the age of fifteen, Foster’s ambition for a proper education led him to open a school in his settlement, as an unlicensed teacher. Excelling in his studies, he won the Kings County Scholarship, which allowed him to enrol in the recently formed University of New Brunswick (UNB) in Fredericton in fall 1865. His fellow undergraduates included two future premiers of New Brunswick, William Pugsley and James Mitchell, as well as the renowned teacher George R. Parkin. Parkin and Foster would develop a friendship that would last for over 50 years. While at UNB, Foster founded the University Monthly, which eventually became The Brunswickan, the campus’ student newspaper that is still in circulation today. He won the Douglas Gold Medal as a freshman and Natural Science First the next year, and he graduated second in his class. Remembering his experience in Fredericton fondly, Foster stated: “The grounding and stimulus received at my Alma Mater I can trace through my whole life as a resourceful and sustaining foundation” (qtd. in Wallace 24). In his twilight years, he would be instrumental in establishing a half a million dollar endowment fund at UNB.

Following his graduation, Foster accepted a position at Victoria County Grammar School in Grand Falls, New Brunswick, at a salary of $600 per annum. In the next few years, he took on new challenges and began to explore in the same way that he would during his political career—taking charge of the Superior School at Fredericton Junction, the Baptist Academy in Fredericton, and then the new Girls’ High School in Fredericton. In 1872, he travelled to Scotland and studied first at Edinburgh University, later at Heidelberg in Germany.

On his return home in 1873, Foster was made a professor of classics and literature at the University of New Brunswick, a position he would hold for six years. While the social machinations of university life seemed to frustrate him, his passion for lecturing carried him through his teaching until he resigned in 1879.

Raised as a Free Christian Baptist, his political and social beliefs were influenced by Baptist teachings. At the age of thirteen he signed a temperance pledge, and as a life-long abstainer, he committed himself to prohibition as a political pursuit for the rest of his career. Following his resignation from UNB, he became a much sought-after temperance orator. For three years after 1879, he toured the continent lecturing, reaching as far as Kentucky and Wisconsin.

Encouraged by a friend, he arrived in Saint John in May 1882 to run for office in the riding of Kings County against incumbent Lieutenant-Colonel James Domville, a long-serving member of John A. Macdonald’s government. Foster ran as an independent Conservative and won by a considerable majority. He was introduced to the House of Commons on 8 February 1883 and readily impressed Prime Minister John A. Macdonald with his clear oratory and debating skills. On the recommendation of his old acquaintance Sir Leonard Tilley, who was then lieutenant governor for New Brunswick, Foster was appointed Minister of Marine and Fisheries in 1885. He would handle this position deftly, bringing to it matchless dedication and organizational skills that would net him the portfolio of Minister of Finance in 1888. In this capacity, he became one of John A. Macdonald’s most respected lieutenants. Foster was re-elected in 1891 and survived a very turbulent time that saw the leadership of his party pass through many hands.

Frustrated with a perceived lack of leadership, Foster was one of seven MPs, including Sir Charles Tupper, to resign in protest from the House of Commons on 4 January 1896. Eventually, the sides reached a compromise that saw the protesting members reinstated, but the Conservatives would be defeated by Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal party that same year. Foster nonetheless ran in York County, winning a majority of nearly 2 to 1 in a new riding.

Four years later, Foster would suffer his first political defeat. In 1900 he again switched ridings to Saint John at the request of his party and was defeated by former premier of New Brunswick A.G. Blair. With this loss, Foster left Parliament for the first time in eighteen years.

In 1903 he ran in a by-election for North Ontario and was defeated again. Not to be dissuaded, the following year he ran in the general elections for North Toronto, where he had been residing since 1901. He overcame the mayor of Toronto, Thomas Urquhart, by a slim majority, and would hold this seat with a steadily increasing majority for the next two decades.

Foster’s political battles were many, but his most passionate issues remained the temperance movement and the implementation of reciprocal trade within the British Empire. He was very critical of Laurier’s attempts at reciprocity with the United States, and when a trade agreement was laid before the house in 1911, Foster warned that this decision was “fraught with consequences greater than any of us can now see” (qtd. in Wallace 151).

In 1912 he was appointed chairman of the Royal Commission on Imperial Trade and spent two years working in Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and China. Partly in recognition of his work with the commission, Foster was knighted in 1914. He was later appointed one of four British representatives at the Allied Economic Conference in Paris in 1916. Shortly after this, he was assigned the title of Imperial Privy Councillor by the King.

On the eve of the general election in 1917, Foster was struck by a railway engine at Union Station in Toronto and left with a broken shoulder blade, a broken collar bone, and four broken ribs. His determination even as an injured 70-year-old was in evidence as he resumed his duties from his sickbed and returned to the House within months.

Foster convinced Parliament to set up the Dominion Bureau of Statistics and institute Daylight Savings Time. In 1918, his long standing fight for temperance was fulfilled as a general prohibition was instituted. That summer, the King conferred upon him the Grand Cross of St. Michael and St. George.

Age finally began to weigh on Foster. He was offered, but declined, the lieutenant-governorship of Ontario as well as the high commissionership in London. He took a brief position as head the Canadian delegation to the First Assembly of the League of Nations at Geneva in 1920. But the following year he decided to end a long career in the House of Commons and retired to the Senate.

As a senator, he became a champion for the League of Nations. In 1922, he was one of the founders of the League of Nations Society in Canada, and he represented Canada at the international assemblies in both 1926 and 1929.

Foster still found the energy to travel to Fredericton. In October 1930, he made the dedicatory address for the unveiling of the Bliss Carman monument in Fredericton. Yet his health continued to decline, and he died in Ottawa on 30 December 1931. He was honoured with a state funeral.

While Foster was acknowledged during his career as a supreme debater and orator, he suffered from an abrasive temperament. He was respected but unpopular: “There was, and always would be, something singularly unappealing about Foster” (Waite 218). He may have entertained ambitions of being Prime Minister during his long career, but his lack of charisma prevented him from rising above his more popular colleagues. He did, however, serve as acting Prime Minister on several occasions.

He published one book, a collection of some of his speeches and lectures, Canadian Addresses (1914).

Matthew Heiti, Spring 2009

University of New Brunswick

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Foster, George Eulas. Canadian Addresses. Toronto: Bell & Cockburn, 1914.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Bridle, Augustus. Sons of Canada: Short Studies of Characteristic Canadians. Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1916.

The Brunswickan. Fredericton: Brunswickan Publishing Inc., 1867–.

<https://www.thebruns.ca/>.

Waite, Peter B. Canada 1874–1896−Arduous Destiny. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1971.

Wallace, W. Stewart. The Memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Sir George Foster. Toronto: Macmillan, 1933.