Stompin' Tom Connors

Charles Tom Connors (9 February 1936–6 March 2013), known by his stage name “Stompin’ Tom,” was an award-winning Canadian country and folk singer-songwriter. A prolific artist, he wrote over 600 songs and released more than four dozen albums over the course of his career. Connors, whose own songs were nationalistic in content, was an advocate for Canadian and regional content and strove to support Canadian musicians.

Connors was born at the General Hospital in Saint John, New Brunswick to Isabel Connors and John Thomas Sullivan. His parents were unmarried due to religious tensions; the Connors were Protestants while the Sullivans were Catholics. For this and other reasons, John Thomas Sullivan was never fully involved in his son’s life. Connors’ first home was on Patrick Street in one of the poorest and most run-down neighbourhoods of Saint John, and he would bounce around from apartment to apartment in the surrounding area with his mother until they left the city and hitchhiked through Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia in search of work. Eventually, Isabel was jailed for stealing groceries and Connors was separated from her and his younger sister Nancy (Connors, Before the Fame 7-8 102). At this point Connors was put into the care of Children’s Aid, spending a brief period of time at St. Patrick’s Orphanage in Silver Falls, New Brunswick before being adopted by Cora and Russel Alyward from Skinners Pond, Prince Edward Island. He ran away when he was thirteen, partially because of disagreements with Cora and partially in the hopes of locating his mother. He hitchhiked back to Saint John where he worked, attended school, and lived in boarding houses. It was in Saint John where Connors bought his first guitar and began writing songs, and it was during a brief return to the Alywards that he first performed at dances in schoolhouses and community halls (Connors, Before the Fame 182).

At the age of fifteen, Connors left the Alywards for the last time and began a thirteen-year hitchhiking odyssey across Canada in search of work, spending the occasional night in jail for vagrancy. This time of Connors’ life, “during which he saw a great deal of the country and experienced the seamy side of life [...] informed his musical persona as a rough-hewn, sincere, grassroots songwriter” (Nygaard King and Green). It was not until 1964, however, that Connors’ musical career officially began with a performance at the Maple Leaf Hotel in Timmins, Ontario. Though he initially performed a few songs in exchange for a beer, the hotel manager was so impressed that he hired him for fourteen months (Connors, Before the Fame 441). Due to poor acoustics at the Maple Leaf and other Ontario hotels where Connors played, he began stomping his foot on the stage to help keep rhythm. Three years later, during a performance at the King George Tavern in Peterborough, Ontario on 1 July 1967, this habit earned him the nickname “Stompin’ Tom,” which would remain with him for the rest of his career. It was also in 1967 that he released his first album, The Northland’s Own Stompin’ Tom Connors. He would go on to release more than four dozen albums through seven different record labels.

Connors’ career became publically significant and several of his songs, including “The Hockey Song,” “Sudbury Saturday Night,” and “Bud the Spud,” were well known across Canada. In addition, he won the Juno Award for Male Country Singer of the Year from 1971–75 and won Best Country Album for his album To It and At It in 1974. His music was unabashedly Canadian in content with a particular focus on the working class and Canadian historical events. His style was also heavily influenced by Maritime country musicians, such as Wilf Carter and Hank Snow, who he first encountered in Saint John (Echard 16). According to critic William Echard, Connors’ “insistence on performing only explicitly ‘Canadian’ material [was] exceptional in Canada’s music industry. [He was a] major force in challenging the assumption that Canadian themes are less worthy than American or blandly ‘universal’ ones” (8). Despite this, and in fact because of it, Connors received little attention from commercial radio. Broadcasters were reluctant to air Canadian country music because they felt it was too regionalist and of poorer quality, a stance Connors disagreed with strongly. This trend toward discounting Canadian content in favour of American or Americanized “pop” music drove Connors into protest. In 1978, he returned his Junos to protest against giving awards to expatriate Canadian artists, and he boycotted radio and performance for what he intended to be only one year, though it stretched into eleven years before he resumed his music career.

Connors’ New Brunswick upbringing had a significant effect on his artistic outlook. His childhood in the blue-collar districts of Saint John instilled in him a working-class ethos that he translated into a unique, populist appeal for the average Canadian listener. Fellow Canadian musician Murray McLauchlan stated that the reason for this appeal was because Connors “wrote songs for the simple working people of Canada about the things in life they recognized” that “no one else was reflecting” (qtd. in Martin). His song “New Brunswick and Mary” illustrates this ability to connect with audiences:

I bet the salmon are all running now up along the old Miramichi

And in Woodstock the potatoes will be doing fine

While way out west in the wheat fields with Mary’s love in my heart

I keep far away New Brunswick in my mind.

The quoted lines encapsulate the song’s greater message of the tension between one’s love of home and the necessity of moving west for financial opportunity. This message, familiar to most New Brunswickers, illustrates his empathy and appeal to the working-class people of his home province and to Canadians generally.

Connors’ support for Canadian content was not limited to his own music. He co-founded Boot Records & Morning Music Publishing in 1971 and founded A-C-T records in 1986 with the goal of promoting Canadian artists, regardless of his own personal feelings of the genres represented (Lumley 269). According to classical guitarist Liona Boyd, who signed with Boot Records in the 1970s, Connors “wasn’t really a fan of classical music but he had heard Canada had no classical label, which was absolutely true. So [...] he decided he’d be the first one” (qtd. in Stevenson). It was for this love of Canada, particularly the East Coast, that St. Thomas University gave Connors an honorary degree (Doctor of Laws) in Spring 1993. The award recognized Connors’ celebration of the Canadian worker, tracing that devotion to the working class to Connors’ New Brunswick beginnings.

When Connors died on 6 March 2013, he left behind a legacy of patriotism and support for Canadian content. His music was greatly informed by working-class values and a distinctly Maritime vision he learned both in his travels across Canada and in his native province of New Brunswick.

Monica Furness, Fall 2015

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources (Chronological)

Discography

Connors, Stompin’ Tom. The Northland’s Own Stompin’ Tom Connors. Rebel Records, 1967.

---. On Tragedy Trail. Rebel Records, 1968.

---. Bud the Spud and Other Favourites. Dominion Records, 1969.

---. Stompin’ Tom Meets Big Joe Mufferaw. Dominion Records, 1970.

---. Merry Christmas Everyone. Dominion Records, 1970.

---. Stompin’ Tom Sings 60 Old Time Favourites. Dominion Records, 1970.

---. Live at the Horseshoe. Dominion Records, 1971.

---. Stompin’ Tom Sings 60 More Old Time Favourites. Boot Records, 1971.

---. My Stompin’ Grounds. Boot Records, 1971.

---. Love & Laughter. Boot Records, 1971.

---. Pistol Packin’ Mama. Cynda Records, 1971.

---. Bringin’ Them Back. Cynda Records, 1971.

---. Stompin’ Tom and the Hockey Song. Boot Records, 1972.

---. To It and at It. Boot Records, 1973.

---. Northlands Zone. Boot Records, 1973.

---. Across This Land With Stompin’ Tom Connors. Boot Records, 1973.

---. Stompin Tom Meets Muk Tuk Annie. Boot Records, 1974.

---. Stompin’ Tom Sings the North Atlantic Squadron. Boot Records, 1975.

---. The Unpopular Stompin’ Tom Connors. Boot Records, 1976.

---. Stompin’ Tom at the Gumboot Cloggeroo. Boot Records, 1977.

---. Stompin’ Tom Is Back to Assist Canadian Talent. Act Records, 1986.

---. Fiddle and Song. Act Records, 1988.

---. A Proud Canadian. EMI Records, 1990.

---. More of the Stompin’ Tom Phenomenon. EMI Records, 1991.

---. Once Upon a Stompin’ Tom. EMI Records, 1991.

---. Believe in Your Country. EMI Records, 1992.

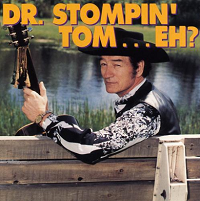

---. Dr. Stompin’ Tom, Eh? Emi Records, 1993.

---. KIC Along With Stompin’ Tom. EMI Records, 1993.

---. Long Gone to the Yukon. EMI Records, 1995.

---. 25 of the Best Stompin’ Tom Souvenirs. EMI Records, 1998.

---. Move Along With Stompin’ Tom. EMI Records, 1999.

---. The Confederation Bridge. EMI Records, 2000.

---. Stompin’ Tom Sings Canadian History. EMI Records, 2001.

---. An Ode for the Road. EMI Records, 2002.

---. Stompin’ Tom and the Hockey Mom Tribute. EMI Records, 2004.

---. The Ballad of Stompin’ Tom. EMI Records, 2008.

---. Stompin’ Tom and the Roads of Life. EMI Records, 2008.

---. Unreleased Songs From the Vault Collection – Vol. 1. Universal Music Canada, 2014.

---. Unreleased Songs From the Vault Collection – Vol. 2. Universal Music Canada, 2015.

Filmography

This is Stompin’ Tom. Dir. Edwin W. Moody. Perf. Stompin’ Tom Connors. Marlin Motion Pictures, 1972.

Across This Land With Stompin’ Tom Connors. Dir. John C.W. Saxton. Perf. Stompin’ Tom Connors. Cinépix and Kit Films, 1973.

Stompin’ Tom’s Canada. Perf. Stompin’ Tom Connors. Prod. Don McRae. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1974–1975.

Stompin’ Tom Live in Concert. Dir. René Dowhaniuk. Perf. Stompin’ Tom Connors. Pillar Media, 2006.

Children’s Fiction

Connors, Stompin’ Tom. My Stomping Grounds. Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1992.

---. Bud the Spud. Charlottetown: Ragweed, 1994.

---. Hockey Night Tonight. Halifax: Nimbus, 2009.

Autobiographies

Connors, Stompin’ Tom. Stompin’ Tom: Before the Fame. Toronto: Penguin Books, 1995.

---. Stompin’ Tom and the Connors Tone. Toronto: Viking Canada, 2000.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

“Dr. Stompin Tom Connors, Eh? – Remembering a Canadian Music Legend.” St. Thomas U. 7 Mar. 2015.

<https://www.stu.ca/>.

Echard, William. “Inventing to Preserve: Novelty and Traditionalism in the Work of Stompin’ Tom Connors.” Canadian Folk Music Journal 22 (1994): 8-22.

Ha, Tu Thanh. “Thank You, Stompin’ Tom Connors. We Needed You.” The Globe and Mail 7 Mar. 2013.

<https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/editorials/thank-you-stompin-tom-connors-we-needed-you/article9441159/>.

Lumley, Elizabeth, ed. “Connors, Stompin’ Tom.” Canadian Who’s Who 2001: Volume XXXVI. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2001.

Martin, Sandra. “Canada’s Troubadour Sang of Everyday Lives.” The Globe and Mail 9 Mar. 2013.

<https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/stompin-tom-connors-canadas-troubadour-sang-of-everyday-lives/article9565495/>.

Nygaard King, Betty, and Richard Green. “Stompin’ Tom Connors.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. 22 Apr. 2013. Historica Canada. 25 June 2020

<https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/stompin-tom-connors-emc>.

Salutin, Rick. “Stompin’ Tom Connors Deserves a Place in the Ranks of Canada’s Poets.” The Toronto Star 8 Mar. 2013.

<https://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2013/03/08/stompin_tom_connors_deserves_a_place_in_the_ranks_of_canadas_poets_salutin.html>.

Stevenson, Jane. “Love for Stompin’ Tom Connors Went Beyond Canada’s Borders.” Toronto Sun 7 Mar. 2013.

<https://torontosun.com/2013/03/07/love-for-stompin-tom-connors-went-beyond-canadas-borders/wcm/1679d149-3ebb-4fea-ae7a-529badf64803>.

“Stompin’ Tom Connors Discloses Reasons for Juno Nomination Withdrawal.” RPM Magazine 22 Apr. 1978.