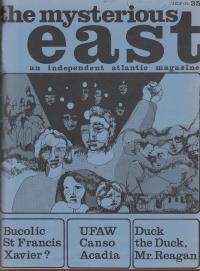

The Mysterious East

The Mysterious East was an alternative news magazine published in Fredericton, New Brunswick from 1969–1972.

The magazine's beginning can be traced to the New Brunswick Supreme Court’s case against Tom Murphy. Murphy, a student/journalist at the University of New Brunswick, was found guilty of contempt of court and spent ten days in jail for writing that the Supreme Court “was a tool for the corporate elite” (The Mysterious East fonds). He made that assessment after attending a hearing in 1968 concerning Norman Strax, a radical professor at the University of New Brunswick who was charged with inciting students over the Vietnam War. The group that would later create The Mysterious East came together to help with Murphy’s defense, and their magazine became a continuation of their activist work.

During the winter of 1969, the group engaged in numerous conversations regarding the state of news media in Canada (particularly the Maritime provinces), the lack of critical journalistic voices, and the need for reporting on serious issues pertaining to Maritime life. That summer they gathered at Donald Cameron’s home in Fredericton with the aim of creating an alternative news magazine or paper. Unsure as to what form the new publication should take, they were certain they wanted to critique current media and provide background information to their news stories.

The fledgling editors of The Mysterious East were Robert Reid Campbell, a graduate student at the University of New Brunswick focusing on the Canadian little magazine and its function in Canadian culture; Russell Arthur Hunt, an assistant professor of English at St. Thomas University who was interested in politics and literature as well as journalism and education; Thomas Peter Warney, a poet, musician, and graduate teaching assistant at the University of New Brunswick; and Donald Cameron, a professor of English at the University of New Brunswick who contributed to a variety of Canadian periodicals and was a commentator for CBC.

Janice Oliver, an interior designer, and Jon Oliver, an architect-planner, worked on the graphics for the magazine. By February 1970, Warney had left the editorial board and John Rousseau had joined as an editor. In May 1970, Ed Levesque and Ralph Littlecock had also joined the editorial board, changing their contribution to that of staff writers four months later. In February 1971, Garry Allen had joined the board, and by November of that year Andrew Scott was also a contributing editor.

“[A] product of people who are fed up, frustrated, [and] angry with rotten journalism” (ME fonds), the editors of The Mysterious East, none of them practicing journalists or knowledgeable about assembling and distributing a news magazine, were unconcerned that they might lose money or that the magazine might fold after one or two issues. Rather, they believed that what was at stake was whether a Maritime audience would support a “fair, hard-hitting and lively” magazine that “objects to the vulgar, the pompous and the dishonest … to tell not only what happened, but why it happened” (ME fonds). On 21 August 1969, letters of patent were issued to Campbell, Hunt, and Warney that incorporated the Rubber Duck Press, the publication and distribution arm of The Mysterious East.

Aimed at monthly (occasionally bimonthly) distribution, The Mysterious East published in-depth provocative articles that focused on important issues of Atlantic life that editors felt were overlooked by the mainstream news media. Although mostly critical in its analysis, the magazine also focused on social aspects, publishing book reviews and interviews with Maritime craftspeople. And whatever the treatment, writers and editors approached their task with humor and wit. In the February/March 1970 issue, for example, a new monthly Rubber Duck Award was introduced that invited readers to nominate a person, corporation, government, or institution that had committed an “astonishing act of foolishness, incompetence or knavery” or general “numbskullduggery” within the last month (ME fonds).

After raising five hundred dollars to pay for the printing of the first edition, editors struggled to find a printer. One printer, for example, explained that he was reluctant to print a magazine that criticized K.C. Irving, who was involved in every major industry in New Brunswick and was the owner of all the major newspapers in the province. The first issue of The Mysterious East was nevertheless released in November 1969.

Although editors had originally set out to publish twelve annual issues of the magazine, they produced twenty-one issues from 1969 to 1972. 5,000 copies of the first issue were printed, and, by 1970, 10,000 copies of the magazine were distributed monthly—and these to a wide variety of readers from across Canada. The twenty-one issues of the magazine contained articles of considerable scope: on the environment, education and schools, housing, drugs, birth control, policing, First Nations, censorship, prisons, industrial politics, poverty, the Acadians and bilingualism in New Brunswick, mass media, the law, and the judicial system.

The magazine operated primarily through volunteer efforts, although a secretary was hired when correspondence became too much for the editors. The magazine relied almost entirely on subscribers for support, supplemented by a small amount of paid advertising. Contributors were not paid for articles.

Using the magazine as a platform, the editors presented briefs to the government concerning mass media, censorship, and poverty. A few of those included a Brief to The Special Senate Committee on the Mass Media (presented to Senator Keith Davey, Chair), a Brief on the Suppression of Information (presented to The Task Force on Social Development in New Brunswick), and a brief to Premier Robichaud concerning the ban on liquor advertising in New Brunswick publications. The editors also drafted petitions calling for government reform. They received a Canada Council grant to publish a national book supplement in their December 1970 issue. They distributed a birth control pamphlet in their magazine published by the Students’ Society of McGill University, and they wrote a boycotter’s guide to politics and pollution.

In October 1970, Gary Allen, Russell Hunt, Donald Cameron, Robert Campbell, and John Rousseau drafted a proposal for The Rubber Duck College of Journalism and Communications, a non-profit institution based on the educational ideas stemming from the free school movement. Just as their dissatisfaction with news media had prompted the creation of The Mysterious East, their discontent with journalism education drove their interest in setting up an alternative school. The proposal described a school with no courses, no credits, and no degrees, one in which students would work closely with five full-time faculty members and “resource people.” The college was to have close ties with the University of New Brunswick, St. Thomas University, and the Fredericton community. The editors sent out copies of the proposal asking for feedback and for volunteers to act as “unpaid resource people to be called upon as the needs of the students require” (ME fonds). The feedback was positive; the main concern pertained to whether the college was financially possible. The editors received letters from numerous people from New Brunswick and central Canada offering to participate in the project, which, despite interest, never got off the ground.

One of the final efforts of the editorial board was to create The Paper Tiger Press to address the paucities and shortcomings of printing opportunities in Atlantic Canada. Local publishers enthusiastically supported the need for a specialized and properly equipped printing plant. The Paper Tiger Press was to be dedicated solely to printing books and periodicals, including The Mysterious East and other cultural documents.

However, like The Rubber Duck College of Journalism and Communications, The Paper Tiger Press was never realized. The reasons were personal, most stemming from the different priorities in the lives of the editors. Cameron’s relocation to Nova Scotia to focus his career on journalism and Hunt and Campbell’s focus on K.C. Irving: The Art of the Industrialist contributed to the abandonment of these projects—and of The Mysterious East.

The Mysterious East project ended in late 1972, taking with it a good deal of literary and cultural energy that, for a time, fired the imaginations of New Brunswickers.

Danielle Lee, Winter 2009

Fredericton, NB

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Hunt, Russell. Personal interview. Oct. 2008.

The Mysterious East fonds. MG L19. Archives & Special Collections. U of New Brunswick Libraries, Fredericton, NB.