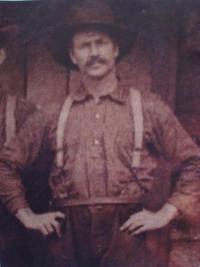

Rovin' Joe Smith

Joseph Samuel Smith (known by his nickname Rovin’ Joe) was a folk poet from Renous, New Brunswick, a rural community located a few kilometers north of the village of Blackville. He was born on 11 June 1872 into difficult circumstances. His father was not listed on his birth certificate and his mother, Mary Ann Sullivan from Lockstead, New Brunswick, was not involved in his upbringing (“Smith, Joseph Samuel”). Rather, Joe was passed around from household to household throughout his childhood and youth (Donovan, Beautiful Blackville 398-99). Nonetheless, Joe attended school in Blackville until he was old enough to work in the lumber business. He was mentored there by Jim Underhill, the father of one of his friends.

Smith’s poetic works mirror his cheerful personality. His style is lighthearted and personal, focussing on mockery, local characters, and playful humour. His most acclaimed works include “A Winter on Renous” (1904) and many short ballads that continue to be sung or recited. He did not, however, publish any of his own work. Rather, his poems and stories were written down by local historians and later published in books about the Miramichi.

In those tellings, Rovin’ Joe had a reputation as the community rascal who loved to torment his neighbors and co-workers. His antics of stealing from the community— either to tease or to give to poorer families— led to his pursuit by a detective by the name of Ring (Donovan, Beautiful Blackville 403). Even during his marriage to Florence O’Brien (solemnized in 1900 and resulting in five children), Smith continued to be known as the local Robin Hood. He died by drowning on 22 November 1912 after falling through the ice at Holmes Lake, New Brunswick during a weekend stay at his boss’ hunting cabin (Sutcliffe 137). He struggled to climb out of the frigid lake, breaking all of his fingers clawing at the ice to save himself (Donovan, Deep and Dark 78).

Joe was especially talented with the two-liner. This one describes his pursuit by the detective: “Detective Ring, you’re on my trail, I guess my boys, I’d better sail!” (Donovan, Beautiful Blackville 403). Another displays his quick-wittedness: “Little bird of little wit, who taught you on my head to shit? But since you’ve been so beastly mean, I’m going to sweep you from that collar beam” (Beautiful Blackville 408). His simple poetic style aimed at drawing in a local audience by emphasising familiar slang and by using known names and stories, sometimes including positive commentary on a person or taunting them to the delight of their neighbours and friends.

“A Winter on Renous” remains a classic for its autobiographical commentary. The poem recounts Smith leaving Renous in 1804 to work logs along the Dungarvon River with the three Hayes brothers. Smith disliked the logging crew and the exhausting routine, which had “no mercy on a man but to work him day and night” (Donovan, Beautiful Blackville 411). Once a winter on the Dungarvon passed, he realized he “loved their ways, in the land of the blest there is peace and rest for his sons and Morgan Hayes” (Beautiful Blackville 413). He thus offers himself as a laureate of hard labour and strenuous conditions, a man who endured crowded logging camps during difficult winters. His Miramichi is a place of strong men, prosperity, and hard-earned respect.

More light-hearted is “The Charming Laura Brown,” which tells the tale of a young Saint John man named William Turner who falls in love with a “cross-eyed, giddy, traveling woman” by the name of Laura Brown. The couple weds and moves to Dungarvon to raise a son named Jimmy, who “would romp all day in the hay, like charming Laura Brown” (Beautiful Blackville 413-14). Smith’s preference for outlandish stories is also reflected in poems like “The Prowlers,” which conveys the tale of Old Michael from Grey Rapids, New Brunswick. Old Michael is preparing to shoot his sister Nancy’s mischievous sons if they ever dare to return again to steal his crab apples. The boys never do return as the “wily young prowlers found pastures more green” and dump his apples instead at his neighbour’s house (Beautiful Blackville 419-420).

Although his name is not well-known provincially, the Dungarvon River’s Rovin’ Joe Smith branded himself a local treasure for his quick-wittedness and audacious statements about those who came into his purview. He did not have the education, background, or cultivation of other New Brunswick writers, but his blunt and humorous style met the tastes of Miramichi listeners, even if it sometimes tried their nerves. He remains an original literary voice along the Miramichi.

Riley Esty, Fall 2018

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Donovan, Ben. Beautiful Blackville Meet the Rushing Renous. Richibucto, NB: Imprimerie Polycor, 2016.

---. The Deep and Dark Dungarvon Sweeps Along. Saint John, NB: Quebecor World Atlantic, 2001.

Magee, Samantha. “A Century After His Death, Legendary Renous Figure's Family Joins in Ceremony at St. Bridget Cemetery.” Telegraph-Journal [Saint John, NB] 1 Dec. 2012: H5.

Manny, Louise, and James R. Wilson. Songs of Miramichi. Fredericton, NB: Brunswick Press, 1970. 110, 187-90.

“Smith, Joseph Samuel.” Ms. RS141A5. Provincial Archives of New Brunswick. Fredericton, NB.

Sutcliffe, Brian. “Miramichi Folksong Festival Hosts-Play.” Times and Transcript [Moncton, NB] 27 Apr. 2013: A4.

---. Stories I’ve Been Told: The Maritime Storytellers of CBC’s Weekend Mornings. Lawrencetown Beach, NS: Pottersfield Press, 2002. 137.