Lorne Joseph Simon

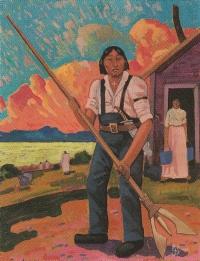

Lorne Joseph Simon (novelist) was born 10 October 1960 in the First Nations reservation of Elsipogtog, New Brunswick (formerly known as Big Cove). His published works include the novel Stones and Switches (1994) and a short story, which was included in the anthology Blue Dawn, Red Earth: New Native American Storytellers. They are both heavily influenced by his upbringing in a First Nations community.

Simon was fluent in speaking and writing the Mi’kmaq language and was raised according to Mi’kmaq tradition. Learning how to fish and hunt were key to living traditionally, as was seasonal readiness (being able to prepare for the harsh Canadian winter). Ice fishing, he learned, was one example of being seasonally prepared. To a traditional First Nations individual, all humans are beings from the earth and he learned accordingly of the importance of offerings to the land as key to the relationship between men and the earth. He learned the rituals of offerings, such as an offering of tobacco given to the land in exchange for the bounty acquired by the hunter.

Simon graduated from the En’owkin International School of Writing in British Columbia in 1992, where he received the Simon Lucas Jr. Award for being the top graduating student. He had just begun a Bachelor of Education Degree at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, New Brunswick, when he died suddenly in a car accident.

The Mi’kmaq-Maliseet Institute of the University of New Brunswick awards a prize each year in memory of Lorne Simon. The prize is awarded to an outstanding First Nations student, with a preference towards promising writers, on the Fredericton campus.

Stones and Switches, Simon’s first and only novel, is set in the 1930s on the fictional reservation of Messkig, one of the Mi’kmaq words for “large.” “It is an ironic name for a reservation,” writes Simon, “that has had most of its lands illegally taken” (152). It tells the story of Megwadesk (a Mi'kmaq word for the “northern lights”) and his common-law partner Mimiges (“butterfly”). Megwadesk is experiencing a struggle between his traditional Native upbringing and the more immediate and alluring white world. His dreams are haunted by the frequent appearance of rabid animals:

There were dark pillows under his reddened eyes. For the past six nights he had slept very little and, of the little sleep he got, none of it had been restful. A dreadful web seemed to surround him, visible only to his shut eyes. Always his spirit's nightly flights ended in a tangle of nightmares. Something always chased him in his dreams. He got no satisfaction from sleep, no rest. So now he avoided sleep. (6)

During an early scene in the novel, Megwadesk comes to the conclusion that almost every Native story featuring ghosts and invisible spirits can be explained away by natural occurrences. Being down on his luck, Megwadesk decides he should try and steal a catch from his friend Skoltch's (“frog”) net. As Megwadesk nears his friend’s boat in the middle of the river, the clouds open up and the moon's light casts down onto Megwadesk and illuminates him as a thief. He panics and flees from sight. Shaken, Megwadesk is now feeling a spiritual tug of war between his traditions and the white world:

It's our silly old beliefs, eh, that keep us from getting anywhere, he thought. Everything's taboo with us, eh. An' these beliefs go deeper than the head. Nisgam, just look at me, eh! Last night I could've taken advantage of Skoltch's net but I ran away instead! An' why? 'Cause I was 'fraid of the spirits getting back at me. An' Nisgam nuduid, even though I know in my head that it's all nonsense, I can't get past what I was raised to believe! (18)

Simon’s story captures life on a reservation expertly, moving from the isolation to the discrimination First Nations people are subjected to by whites.

On 8 October 1994, Simon was driving home to see his family (parents Sarah and William John Simon Sr., and brothers Adam and Jesse Simon) on the Elsipogtog Reservation for Thanksgiving when his life tragically ended in a car accident. Nine months prior, the editorial committee at Theytus Books had chosen his Stones and Switches to be the first publication by an En’owkin International School of Writing graduate. On the day of the accident, the final proof of his novel was in the mail on the way to him for his approval. At the discretion of the Simon family, Theytus decided to proceed with the release of Stones and Switches as planned.

Marjorie Retzleff, a contributing writer for the Canadian Book Review Annual, reviewed the book and noted the influence Simon might have had, had he not died:

This first-rate novel about Native Canadian life is presented in the voice of a Native Canadian, with a large amount of credit going to the En’owkin International School of Writing, which recognized and encouraged that voice. Unfortunately, the novel must stand as a memorial to its author, Lorne Simon, who died in a car accident at the time the book was going through its final proofreading. Canadian literature has lost a writer of great potential.

This powerful and engrossing novel is liberal in its use of Micmac words (a glossary is included). Although the point of view is third person, the reader feels fully involved in Megwadesk's spiritual struggles. The climax, which features a mystical dream sequence, is brilliantly surrealistic. This is a wonderful book. (3081)

Simon was passionate about cultural heritage and revitalizing the important aspects of First Nations culture he experienced. In a letter he wrote to Jeannette Armstrong, the Director of En'owkin International School of Writing, Simon highlights what he was hoping to do in his work:

You recently spoke to the public on the excitement you felt about the work Native writers will be doing in the future in reclaiming and revitalizing our past and our cultural heritage. I feel that I am a part of this… Currently there are hardly any Micmac writers who are vigorously taking part in this effort, yet I am sure that I will be setting an example and that others will follow. What I am doing is a ripple emanating from a pearl thrown into the pool of talent. Keep throwing pearls into the pool, for they are not wasted.

Had Simon survived, perhaps he would have led a Mi’kmaq literary revitalization and brought Aboriginal authors into the spotlight of Canadian Literature.

Corry Melanson and George Jacques, Winter 2009

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Simon, Lorne. Stones and Switches. Penticton, BC: Theytus, 1994.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre. Faculty of Education, U of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB. Dec. 2009

<https://www.unb.ca/mwc/>.

Native American Authors Project. The iSchool at Drexel, College of Information Science and Technology, Philadelphia, PA. Dec. 2009

<https://www.ipl.org/div/natam/bin/browse.pl/A405>.

Retzleff, Marjorie. Rev. of Stones and Switches, by Lorne Simon. Canadian Book Review Annual. Ed. Joyce C. Wilson. Toronto, ON, CBRA, 1996. 3081.