Thomas Hill

Thomas Hill was said to be “one of the most intriguing literary figures to walk the streets of Woodstock, Saint John, and Fredericton […]” (Mullaly 1). We would know nothing about his past if it were not for his libel case with The New Brunswick Reporter. This case forced Hill to give an account of his personal history as part of its proceedings.

He testified that he was born in Cornwall, England, in 1807, and then sailed from Plymouth to Quebec City early in 1831. After spending four years in Quebec, where he worked in the carpenter’s trade, he moved to Grand Falls, New Brunswick. While there, Sir John Caldwell hired him as a carpenter for the summer. Next, he travelled south to Woodstock, and then west across the border to Bangor, Maine. He worked until the following June, then moved to Orono, where he, his wife, and three children stayed from June 1836 until 1839. He briefly joined the U.S. army, but quickly deserted. He received a formal charge of desertion, which was printed as a letter in James Hogg’s The New Brunswick Reporter and Fredericton Advertiser on 12 March 1858. This letter led to the libel suit against Hogg. The court ruled in favor of Hogg; however, Hill tried to argue that he had been a civilian who strongly opposed the American position in the “Aroostook War,” which led him to voluntarily leave the United States (Swanick). In December 1839, leaving his family behind, Hill packed his tools and headed back across the border to New Brunswick, where he spent the rest of his life. For a year and a half, he lived in Woodstock practicing his craft and developing his reputation as a writer of songs, a musician, and a wood carver. After this, he moved to Saint John where he worked once again as a carpenter (Mullaly 11).

Hill was involved in many projects once he returned to New Brunswick. He became editor of the weekly newspaper the [Saint John] Loyalist in 1842, a position he held for ten years. In September 1842, he was responsible for the launch of the tri-weekly Aurora (Saint John), but it only lasted for one issue. In Fredericton in 1845, Hill and his partner James Doak (a printer), started The Wreath, which also only lasted for one issue. Throughout the 1840s, he was a key legislative reporter in the province, and many of the reports published in newspapers other than the Loyalist were often credited to him, especially reports from the House of Assembly (Swanick).

While in Fredericton, Hill was active in the Orange Order and was a founding member of the provincial Grand Lodge in 1844. He was also rumored to have remarried at this time, possibly the daughter of Roman Catholic innkeepers Jane and John McDowal. Hill was very forward in his feelings towards other politicians and editors. The most significant of his confrontations occurred in 1844, and concerned the forces of liberalism and responsible government personified by Assemblyman L.A. Wilmot. The Loyalist had strong interactions with England and Hill was ready to attack any representative who proclaimed an anti-royalist sentiment publicly (Mullaly 3).

Hill was also a playwright. Provincial Association: Or, Taxing Each Other was his first play, written in 1845. The play was a tragicomedy that centred on the recently founded Provincial Association which had been formed to combat the government’s policy on free trade. The opening of the play was planned for 3 March 1845 in Saint John; however, supporters of the policy prevented its showing. Performance of the play was disrupted several times by rioting before it was actually presented (Mullaly 44).

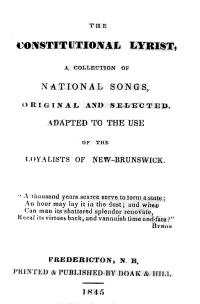

Hill compiled two other notable works. The first, in 1845, was a collection of songs entitled The Constitutional Lyrist: A Collection of National Songs…Adapted to the Use of the Loyalists of New Brunswick. Some of the most popular included “Anniversary Song,” “New-Brunswick Volunteers,” “Fare Thee Well,” and “New-Brunswick Girls.” A second similar work was released five years later, entitled A Book of Orange Songs. This book contained one of Hill’s longest poems, entitled “What is Life?” It speaks about various stages of childhood and maturity. In the last lines of the poem, Hill asks the perspective of a dying man:

He gazed - words came to his relief -

His voice was thick, his answer brief:

"'Tis, when with age and sorrows bent,

To look back on a life well-spent -

'Tis, when afflicted by his rod,

To joy to meet a pard'ning God!

To draw o'er other's faults a blot,

And be contented with your lot.

To part from all below in love,

And hope for happiness above!"

He paused - I gazed upon the clay;

But as the spirit passed away,

Methought I heard a voice from Heaven

Sing - "This is life - to be forgiven!"

Hill is also the author of two well-known poems that both appeared in New Brunswick newspapers. “The Bluenose Boys” was printed anonymously in his newspaper the Loyalist and also in the Conservative Advocate (Fredericton) on 18 July 1844, and “The Emigrants Christmas Song” was published under his name in the New Brunswick Courier on 26 December 1844. Theatre critic Mullaly quotes the following lines:

A rebel band some years ago,

By traitors led astray,

Our social order would o'erthrow

And mar Britannia's sway;

But some were slain, and some are fled,

Some suffering for their crimes.

And may we keep, from all dread,

Our good old Christmas times.Then cheerly sound each festive hall,

And social be your cheer,-

A merry Christmas unto all,

And a prosperous New Year!

And may it be the happy fate,

Of all who read these rhymes,

For many a year to celebrate

The good old Christmas times.

On 13 October 1860 Hill died in Fredericton and was given a pauper’s burial. Even though he often fuelled controversy with his editorials and views, he was an able writer with strongly held opinions who contributed greatly to freedom of the press in New Brunswick. It is unfortunate that so much of his material has been lost. In the words of W.G. MacFarlane, Hill gave “evidence of a nature of fire that flamed at times into vivid flashes of genius and again into the consuming fires of debauchery” (qtd. in Swanick).

Melissa Mountain, Fall 2010

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Hill, Thomas. A Book of Orange Songs. Fredericton, NB: n.p., 1850.

---, ed. The Loyalist. Fredericton, NB: n.p., 1848. [3 Jan.–29 June 1848].

---. Provincial Association, or, Taxing Each Other. Play. 1845.

Hill, Thomas, and James Doak. The Constitutional Lyrist: A Collection of National Songs, Original and Selected, Adapted to the Use of the Loyalists of New-Brunswick. Fredericton, NB: n.p., 1845.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Harper, J.R. Historical Directory of New Brunswick Newspapers and Periodicals. Fredericton, NB: U of New Brunswick, 1961.

MacNutt, W.S. New Brunswick: A History, 1784–1867. Toronto, ON: Macmillan of Canada & Hunter Rose Co. Ltd., 1963.

Mullaly, Edward. Desperate Stages: New Brunswick’s Theatre in the 1840s. Fredericton, NB: Fiddlehead Poetry Books & Goose Lane Editions Ltd., 1987.

---. “The Saint John Theatre Riot of 1845.” Journal of Theatre History in Canada 6.1 (Spring 1985): 44-55.

---. “Thomas Hill: The Fredericton Years.” Studies in Canadian Literature 11.2 (Fall 1986): 190-205. Literature Online. 18 Feb. 2010

<https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/SCL/article/view/8048/9105>.

Smith, Mary E. “The Saint John Theatre Riot.” The Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre. Ed. Eugene Benson & L.W. Connolly. Toronto, ON: Oxford UP, 1989: 372-375.

---. Too Soon the Curtain Fell: A History of Theatre in Saint John, 1789–1900. Fredericton, NB: Brunswick Press, 1981.

Swanick, Eric L. “Biography of Thomas Hill.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 8. Toronto, ON: U of Toronto P, 1985. Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. 2000. U of Toronto/U Laval. 9 Feb. 2010

<http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hill_thomas_8E.html>.