Sarah French

Sarah (French) MacLauchlan (novelist) was born in England in 1792. Her father, Captain William French, was a military officer and was able to provide her with a good education. In 1842, she arrived in Saint John, New Brunswick as a widow with her three teenage children: William, Louisa, and Lucy. In 1850, she married a barrister by the name of William MacLauchlan from Victoria County. They were married in the Victoria County Andover Parish but resided in Saint John to remain close to Sarah’s children. Sarah died in Saint John on 15 February 1872. Although she adopted the name MacLauchlan, she is referred to most often as Sarah French. Her two novels, Letters to a Young Lady on Leaving School and Entering the World (1855) and A Book for the Young (1856), are both works of juvenile literature.

Sarah French is best described as New Brunswick’s “pioneer writer of juvenile literature” (Cogswell 123). In the first half of the 19th-century most writing by women took the form of short sketches, diary entries, letters, and short fiction. Literary critic and historian Fred Cogswell acknowledges that it was not until 1810 that professional novelists emerged in the region (123). During this time fiction writers like Sarah French published works to “popularize moralistic doctrines” (123). In Cogswell’s opinion these types of work provide genuine insight into the social conditions of the time, cautioning, however, that their morals get in the way of reality and as a result their plots appear “contrived and unnatural” (123).

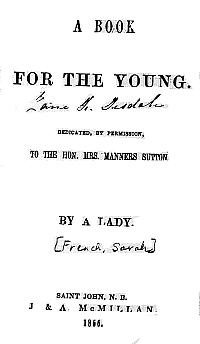

A Book for the Young (1856) is a mix of short stories and poems that encourage young adults to reflect on their lives and their relationship with God. French begins by addressing her audience with a summary of moral advice to consider during the Christmas holiday:

A heartfelt greeting to you, my young friends; a merry Christmas and a happy New Year to you all. Of all the three hundred and sixty-five days none are fraught with the same interest—there is not one on which all mankind expect so great an amount of enjoyment, as those we now celebrate: for all now try not only to be happy themselves, but to make others so too. All consider themselves called on to endeavour to add to the aggregate of human happiness. Those who have been estranged, now forget their differences and hold out the hand of amity; even the wretched criminal and incarcerated are not forgotten. (4)

She continues throughout to focus on the importance of gratitude, moral growth, and prayer, placing each in a Christian context.

Letters to a Young Lady on Leaving School and Entering the World (1855) is a compilation of letters written between the author and her godchild Anna in England. Anna has just turned eighteen and the author gives her advice on perfecting her education and her behaviour as a young lady. French stresses the idea that education is continuous and the completion of schooling does not mean one has completed her education. Specifically, French describes education as “that which inculcates good principles, cultivates reason, subdues the passions and regulates the temper” (3). Despite the author’s emphasis on education, she cautions her godchild on the consequences of pursuing certain career paths: “if you ever think to become a wife, never venture in the paths of literature: a woman who seeks notoriety in them is rarely calculated for the quiet detail of domestic duty” (49). In extending that advice, says one critic, Sarah French formulates the opposition between domestic femininity and the practice of writing for publication that was present in society during their time (Dean 41).

Letters to a Young Lady on Leaving School and Entering the World is referred to, Dean continues, as pioneer conduct literature (18). This type of literature, he says, taught that femininity is an absolute value which cannot be changed simply by a change in geographical location (18). In her epistolary novel, Sarah French agrees, rejecting the idea that standards of behaviour for women may vary by culture: “right and wrong are of no country, or rather they belong to all and the same rule of duty: the same standard of correctness of behaviour pertains to all places and people” (67). In the period from 1820 to 1870, the idea that standards of behaviour might change, or had changed, when British immigrants crossed the Atlantic was strongly resisted in these books of conduct (Dean 18), making them valuable sources of moral information about their time.

Colleen Harrington, Winter 2010

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

French, Sarah. A Book for the Young. Saint John: McMillan, 1856.

---. Letters to a Young Lady on Leaving School and Entering the World. Boston: Crosby, Nichols, 1855.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Cogswell, Fred. “Literary Activity in the Maritime Provinces (1815–1880).” Literary History of Canada: Canadian Literature in English. Ed. Carl Klinck. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1965. 116-138.

Dean, Misao. Practicing Femininity: Domestic Realism and the Performance of Gender in Early Canadian Fiction. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1998.

“Notice of Marriage.” St. John Daily Telegraph and Morning Journal. 29 Oct. 1870: A2.

Probate of Sarah French. 1872. MS. Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Fredericton.