Sheriff Walter Bates

Walter Bates was born on 14 March 1760 in Darien, Connecticut. The fourth son of John Bates and Sarah Bostwick, he was raised as a farmer, a devout Anglican, and a strong Loyalist. “Given his genuine piety and reliable, unadventurous disposition,” said Fred Cogswell, Bates “would probably have remained in that state and station” (DCB 53). However, life had adventure in store for him, and instead of a quaint farm life he found himself among the first Loyalists to settle in Kingston, New Brunswick, where his time as Kings County High Sheriff compelled him to pen one of New Brunswick’s most widely circulated novels, The Mysterious Stranger (1817).

Bates’ idyllic farm life in America was interrupted when he was captured by rebel sympathizers of the American Revolution. Only fifteen years old, he was subjected to torture in an attempt to learn the location of his brothers and their Tory cohorts thought to be hiding in the vicinity (Cogswell DCB 53). Once released, Bates fled his community and lived in the mountains for two years (Hannan CBD 88) before joining a Loyalist farming community in Long Island, where he taught for a number of years. In 1783, Bates joined 100 Loyalists who accepted King George III’s offer of 200 acres of land in Nova Scotia, the name for a territory that included present-day New Brunswick. They set off aboard the Union with two years of provisions. Bates kept a record of the vessel’s journey and its passengers’ early settlement in the posthumously published Kingston and the Loyalists of the “Spring Fleet” of A.D. 1783 (1889).

Bates settled in Kingston, now a small community on the Belleisle Creek of Kings County, New Brunswick. He quickly rose to a position of authority in the settlement through his involvement in the founding of Kingston’s Trinity Anglican Church, where he was a pillar in the Kings County Anglican community until his death on 11 February 1842 (Cogswell DCB 53). His marriage to Abigail Lyon on 7 October 1784 was the first in the township (Hannan CBD 88). They had four children, three of whom died in childhood. He had a second marriage to Lucy Smith (Cogswell DCB 53).

While working as selectman and High Sheriff of Kings County, Bates encountered a horse thief and con man known variably as Henry More Smith, Frederick H. More, William Newman, and Henry J. Moon. Pursued and arrested for stealing the horse of William Knox on 20 July 1814 (Mysterious Stranger 9), Moon landed in the Kings County jail overseen by Bates and jail keeper John Dibblee. Between the years 1812 and 1815, Bates witnessed a series of extraordinary events associated with Moon’s incarceration: his escapes from chains and bars, his theatrical fool-like behaviour, and his elaborate troupe of dancing marionettes fabricated from materials in his cell.

Bates began documenting those strange and extraordinary events. His motivation, it seems, was not only to write a novel (Skene-Melvin 21), but also to record the early history of New Brunswick by documenting the lives of its remarkable individuals (Nadel 113). Bates’ record of Moon thus includes references to important men of the region, local customs, landscapes and landmarks, as well as letters, newspaper publications, and official documents (MacFarlane 8). Bates also recorded his encounters with Moon to serve as an example of the consequences of transgression for those living in his community (Cogswell “Literary Activity” 109). The novel suggests, finally, that Bates also had personal motives for such detailed documentation. In short, he wanted to remove himself from suspicions of shoddiness or complicity in the case: that is, “To enable the Sheriff and Gaoler to traverse the indictments found against them for suffering him to escape from prison” (Mysterious Stranger 5).

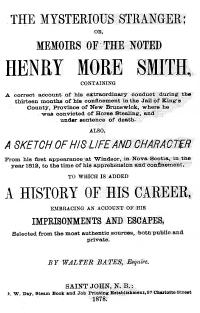

Bates eventually published his record in 1817 in New Haven, Connecticut under the title The Mysterious Stranger; or, memoirs of Henry More Smith; alias Henry Frederick Moon. Since that first publication there have been nine known editions published and several thousand copies sold (MacFarlane 8). Today, the book holds a place of prominence in New Brunswick history and mythology. Moon’s escapades are the source of tall tales for the New Brunswick tourism industry, his nickname adorns one of Fredericton’s popular bars, The Lunar Rogue, and his personal wiles speak to a myth of conniving self-reliance to which New Brunswickers readily relate.

Cogswell attributes the remarkable reception of Bates’ novel to its larger-than-life and “altogether puzzling” protagonist, calling attention, as well, to Bates’ arresting style, which is “comparable to the best work of Daniel Defoe in combining suspense with credibility” (DCB 53). Imagined as a biography more than a work of fiction, the novel presents itself as concerned with fact. “I shall confine myself,” writes Bates, “wholly to statement of facts … I pledge myself, and every other person named in the narrative for the truth of what is related of him while in my custody” (8). While this focus on fact adds to the seeming veracity of the tale, it also emphasizes the intrigue that surrounds Moon, such as the descriptions of the mechanisms used to imprison him and the artistry and extraordinary nature of his escapes. For the critical community, this manipulation of detail and clear narrative awareness is where the novel’s intrigue lies.

Some critics read Bates as an “easily duped enthusiast” (MacFarlane 8), others as straining towards the supernatural (Grantmyre 12). Critic Peter Sanger thinks that Bates is anticipating twentieth-century magical realism, later employing Bates and Moon as allegorical figures in his own creative work to explore the gap between the imagined and the real, nature and artifice, saying and doing, word and world (Jernigan 122). In John Stokes’ Horse, Sanger’s poetic interpretation of The Mysterious Stranger, Sanger casts the reader in the role of Bates, and the poet in the role of Moon, who despite being bound by physical chains (in this case, language) always escapes his pursuer (Jernigan 122, 130). So it is with the poet chained by language. The novel, then, at least for Sanger, is an allegory for how meaning is achieved in poetry.

We will never know if Bates intended to create a magic-realist, self-referential novel or if he simply became enamoured of Moon’s elaborate and delightful cons. In spite of that, there is no denying that The Mysterious Stranger arouses in readers “a spirit of inquiry and investigation” (Raymond 3) that encourages the kind of play and intrigue that have kept the novel alive for two hundred years.

Sharisse LeBrun, Spring 2016

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Bates, Walter. Kingston and the Loyalists of the “Spring Fleet” of 1783 with Reminiscences of Early Days in Connecticut. Saint John, NB: Barnes and Co., 1889.

---. The Mysterious Stranger, Or, Memoirs of the Notorious Henry More Smith: Containing a Correct Account of His Extraordinary Conduct During the Thirteen Months of His Confinement in the Jail of Kings County, Province of New Brunswick, Where He Was Convicted of Horse Stealing, and Under Sentence of Death: Also a Sketch of His Life and Character, from His First Appearance at Windsor, in Nova Scotia, in the Year 1812, to the Time of His Apprehension and Confinement: to Which Is Added a History of His Career Up to the Latest Period Embracing an Account of His Imprisonments and Escapes, Compiled from the Most Authentic Sources. New Haven, CT: Malty, Goldsmith & Co., 1817.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Cogswell, Fred. “Bates, Walter.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 7 (1836–1850). Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1988. 53.

---. “Literary Activity in the Maritime Provinces (1815–1880).” Literary History of Canada. Ed. Carl F. Klinck. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1965. 102-124.

---. “The Maritime Provinces (1720–1815).” Literary History of Canada. Ed. Carl F. Klinck. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1965. 71-83.

Flemming, Patricia L. “Bates, Walter.” Atlantic Canadian Imprints: A Bibliography, 1801–1820. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2015. 121.

Grantmyre, Barbara. Lunar Rogue. Fredericton, NB: Brunswick Press, 1963.

Hannan, Caryn. “Walter Bates.” Connecticut Biographical Dictionary. 2008–09 Ed. Vol.1 A-B. Hamburg, Conn: State History Publications, 2008. 88-89.

---. “Walter Bates.” Connecticut Historical Dictionary. Ed. Russell Lawson. Temecula, CA: Library Reprints, 2008. 81.

Hilder, Kathryn. “Bates Family Papers: 1789–1859, 1895.” UMI: MIC-Loyalist FC LFR.B3F3P3. The Loyalist Collection. Archives and Special Collections, Harriet Irving Library, U of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB.

“An Historical ‘Bonanza’ on Archives Website.” Silhouette: The Associates of the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 29 (Fall 2009): 2-3.

Jernigan, Amanda. “The Ingeminate Eye: Peter Sanger’s Public Poetics.” Public Poetics: Critical Issues in Canadian Poetry and Poetics. Ed. Bart Vautour, et al. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2015. 121-134.

Jones, William. The Loyalists in New Brunswick: Walter Bates and the Settlement of Kingston. Saint John, NB: U of New Brunswick, 2007.

MacFarlane, William Godsoe. “Walter Bates.” New Brunswick Bibliography: The Books and Writers of the Province. Saint John, NB: Sun Printing Co., 1895. 8-9.

Marquis, Greg, and Michel Boudreau. “When Burglary was a Capital Offence.” New Brunswick Criminal Justice History. Fredericton: U of New Brunswick, 2011. <http://www.unb.ca/saintjohn/arts/projects/crimepunishment/justicesystem/burglary.html>.

Nadel, Ira B. “Biography.” Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada. Ed. W.H. New. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2002. 113-117.

Raymond, W.O. “Introduction.” Kingston and the Loyalists of the ‘Spring Fleet’ of 1783 with Reminiscences of Early Days in Connecticut. Saint John, NB: Barnes and Co., 1889. 3-4.

Sanger, Peter. "Catching Breath: 'Abatos' & Others." Aiken Drum. Kentville, NS: Gaspereau Press, 2006. 125-131; 136. [See also Peter Sanger's poem "Abatos" in Aiken Drum, 51-70.]

---. John Stokes’ Horse. Kentville, NS: Gaspereau Press, 2012.

Skene-Melvin, David. “Canadian Crime Writing in English.” Detecting Canada: Essays on Canadian Crime Fiction, Television, and Film. Ed. Jeannette Sloniowski and Marilyn Rose. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2014.19-54.