Emily Elizabeth Beavan

Emily Elizabeth (Shaw) Beavan was born c. 1818 in Belfast, Ireland, and died in Sydney, Australia, on 6 August 1897. She was one of at least five children born to Samuel and Isabella Adelaide (McMorran) Shaw.

As a child, Emily Shaw lived with her family in Belfast, Ireland. As Fred Cogswell tells us, her father Samuel was a master mariner, and as the captain of the Amaryllis, he made numerous journeys between Belfast and Saint John, New Brunswick. As a result, Emily would already have heard stories of New Brunswick’s development when she and her siblings—including her brother and fellow writer, Pringle—arrived in Saint John sometime around 1836. Shaw’s name first appears in school records as a student around this date. She was granted her teacher’s license on 18 September 1837 in Sussex, Kings County.

Less than a year later—on 19 June 1838, at the age of 20—Emily married Frederick William Cadwallader Beavan (28 August 1808–2 August 1867), a fellow teacher and surgeon to the Queens County militia. The couple settled in Long Creek, New Brunswick, where they lived for some time in a house with one acre of land. Finding their plot insufficient for farming, the Beavans purchased a lot of two hundred acres two miles away in English Settlement, Mount Auburn. They had planned on taking their house with them. It was around this time that Emily began writing, and in her first book she describes the process of moving the house using thirty yoke of oxen and two huge hewn trees on sled runners.

While farming and petitioning to teach in Queens County, she contributed at least nine tales and six poems to New Brunswick’s first quasi-literary magazine, Robert Shives’ Amaranth (Saint John, 1841–3). She signed her early contributions as Mrs. B–N, but would later sign her poems as Emily.

Much of her literary inspiration appears to have stemmed from her own life experiences. Several of the tales and poems published in Amaranth, though romantic in nature, give a nod to her Irish roots. The poem “Song of the Irish Mourner” and the tale “Story of Deara, Princess of Meath” are two obvious examples. Her short story “Recollections of Tombe St.,” though presumably a fictional story of romance and marriage, is set near her childhood home in Belfast. The heroines of her tales are often beautiful women of high station or modest wives whose fidelity is challenged in extraordinary ways. To modern readers, Beavan’s gothic-inspired tales may seem improbable, but the pirate threats she describes would have been recent history in the early-nineteenth-century, when American privateers terrorized Atlantic waters.

Beavan incorporates significant detail into all of her short stories, and her prose possesses a poetic quality:

’Twas a fair and happy spot, that lowly Manse of Glenallon, with its shadowing trees and fluttering roses, where the lovely face of Mary beamed amid the flowers she hung on the arm of Morton, listening to his converse, which to her contained knowledge and wisdom, deeper than she thought belonged to earth. (“A Tale of Intemperance” 283)

The world she builds is remarkably visual and atmospheric. Natural imagery is a favourite device and contributes to the authenticity of the backwoods settings she creates.

Events from her seven years spent in New Brunswick had a profound effect on Beavan, and several of her published works recollect her experiences from that time. Her poem “The Lost Children,” published in 1843, is based on a story she was told of two New Brunswick children who were lost in the woods for several years, their fate unknown. Mrs. Beavan’s poetic style is lyrical, and, as with her prose, her true strength lies in the emotive detail with which she describes this mother’s pain:

Many a hope she treasured

In Sorrow’s gloom had burst,

But still her spirit knew

No grieving like the first.

Along her faded forehead

The hand of time had crost,

And every furrow told

Her mourning for the lost. ( “A Vision” 141-8)

As this excerpt demonstrates, Beavan’s poetic forms are usually simple, consisting of couplets or alternating rhymes. Many of her pieces also take on a nostalgic tone like that voiced above, particularly those poems related to motherhood or her Irish roots.

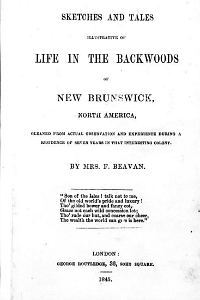

With their children, Alfred and Isabella, the Beavans left their life as New Brunswick pioneers and returned to England in 1843, where Dr. Beavan was to occupy the position of his recently deceased father as surgeon at the Derwent Mines in Blanchland, Northumberland. Their time there was marked by the publication of Emily’s first book, Sketches and Tales Illustrative of Life in the Backwoods of New Brunswick, North America, Gleaned From Actual Observation and Experience During a Residence of Seven Years in That Interesting Colony. The book was published by George Routledge in 1845. Intended as a handbook for prospective settlers, it gives a detailed account of Emily’s observations of a pioneer’s life and living conditions during the 1830s and ’40s. The book is composed of vignettes of daily life in the backwoods of New Brunswick, accounts of the woodsfolk among whom she lived, and samples of her poetry. Customs developing in the province of New Brunswick in the early-nineteenth-century are also well documented. Fred Cogswell praises Sketches for its detailed and lively account of the conditions of daily life:

Not only is information presented more systematically and objectively in Mrs. Beavan’s book, but it covers a much wider range of settlement life, extending to such areas as education, religion, the details of farming and lumbering operations and the reasons why they are so conducted, the significance of the timber trade, the consequences of the imposition of copyright regulations in British North America, the effect of the frontier upon speech patterns and of the climate upon women’s skins.

Beavan has been criticised by modern reviewers for painting an inaccurate and idealistic picture of the lives of those in the settlement. For some, she is too overtly moralistic and uplifting. Cogswell suggests that she is at her weakest in her attempts to be literary, as her language and lyricism are not consistent with her lofty style.

In spite of these complaints, the importance of Beavan’s contribution to New Brunswick literature must not be overlooked. As a result of the wide range of subjects it touches upon, Sketches has become an important resource for those wishing to study the history of New Brunswick, including its early practices of education, agriculture, and forestry. It provides rich insight into early print culture in the Maritimes, and historian Margaret Conrad cites it as a valuable source of literary heritage for women in the Maritime provinces. Sketches has also been used as a resource for those interested in genealogy, for though she makes little or no mention of her own family, the author does detail the affairs of several other families in the area.

Beavan’s book was republished in 1980 as Life in the Backwoods of New Brunswick by Print ’n Press Publications in St. Stephen, New Brunswick. This edition has since gone out of print. Copies may be found in several libraries, and a full-text version is available online.

Canada’s Early Women Writers database indicates that on 29 June 1852, the Beavans and their two eldest children arrived in Australia, where they eventually settled in Kilmore. After being widowed in the summer of 1867, Emily moved in 1881 to Sydney, Australia. She continued to write, contributing to Eliza Cook’s Journal and publishing poems in her local papers. It appears that she also had several other books published by J.W. Partridge & Co. in London. Among them are Alicia, Olga Norvonne, Readings in Rhyme, and Lil Grey: Or Arthur Chester’s Courtship, an original copy of which exists in the British National Library.

Emily Beavan died on 6 August 1897 at the home of her eldest son, Alfred, in Surrey Hills, Sydney. She is buried in an unmarked grave in the Church of England cemetery. Upon her death, a short notice was printed in the Kilmore Free Press describing her as “an amiable kindly lady, [who] was possessed of considerable literary ability” (“Notice”).

Laurie MacKenzie, Winter 2011

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

Beavan, Mrs. Frances. “Adelaide Belmore.” Amaranth 1 (May 1841): 136-40.

---. “Edith Melbourne.” Amaranth 1 (Sept. 1841): 269-74.

---. “The Enthusiast.” Amaranth 2 (Oct. 1842): 312-16.

---. “The Lost Children.” Amaranth 3 (Sept. 1843): 231-3.

---. “The Lost One.” Amaranth 1 (July 1841): 193-202.

---. “Madelaine St. Clair.” Amaranth 1 (Dec. 1841): 353-6.

---. “The Mignonette.” Amaranth 3 (Oct. 1843): 325.

---. “The Mother’s Prayer.” Amaranth 2 (Aug. 1842): 209.

---. “On Prayer.” Amaranth 2 (Sept. 1842): 286.

---. “Recollections of Tombe St.” Amaranth 1 (June 1841): 171-81.

---. Sketches and Tales Illustrative of Life in the Backwoods of New Brunswick, North America, Gleaned From Actual Observation and Experience During a Residence of Seven Years in That Interesting Colony. Newcastle, London: J. Blackwell, 1845.

---. “Story of Deara, Princess Meath.” Amaranth 2 (Mar. 1842): 79-81.

---. “Song of the Irish Mourner.” Amaranth 1 (Aug. 1841): 246.

---. “A Tale of Intemperance.” Amaranth 2 (Sept. 1842): 281-6.

---. “A Tale of New Brunswick.” Amaranth 1 (Nov. 1841): 330-6.

---. “A Vision.” Amaranth 2 (Dec. 1842): 362-3.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

“Beavan, Emily Elizabeth Shaw.” Canada’s Early Women Writers. Simon Fraser U. 27 Sept. 2011

<https://cwrc.ca/islandora/object/ceww%3A0e4362cf-e4fd-4048-b9f8-d93545232343>.

Cogswell, Fred. “Shaw, Emily Elizabeth (Beavan).” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 7. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1988. Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. 2000. U of Toronto/U Laval. 27 Sept. 2011

<http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=3656>.

Conrad, Margaret. “The Birth of Canada’s Past: A Decade of Women’s History.” Acadiensis 12.2 (1983): 140-62.

Dagg, Anne Innis. The Feminine Gaze. Toronto: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2001.

Downie, Alicia Marie. “Emily Elizabeth Shaw (1818–1897).” A Celebration of Women Writers. Ed. Mary Mark Ockerbloom. U Penn Libraries, n.d. 27 Sept. 2011

<http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/beavan/beavan.html>.

Halpenny, Francess G. “Problems and Solutions in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 1800–1900.” Re(dis)covering Our Foremothers: Nineteenth-Century Canadian Women Writers. Ed. Lorraine McMullin. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P, 1990. 37-48.

“The Late F.W.C. Beavan, J.P., Surgeon &c.” Kilmore Free Press 8 Aug. 1867: n.p. Trove Newspaper. 1 Dec. 2011

<https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/70061887>.

“Notice of Death.” Kilmore Free Press 19 Aug. 1897: n.p. Trove. National Library of Australia. Canberra, Aus. 30 Oct. 2011

<https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/61119761>.