The Busy Body

On 28 February 1789, The Busy Body, a play written by English playwright Susanna (Freeman, Carroll) Centlivre in 1709, gained status as the first theatrical performance to take place in the newly formed province of New Brunswick. The comedy was performed in the Long Room at Mallard’s Tavern on King Street in Saint John (Smith, Too Soon the Curtain Fell 2).

The audience that watched the play was described as a “most numerous and polite Assembly,” gathered to watch the cast of young amateur Loyalist gentlemen perform The Busy Body, accompanied by the afterpiece Who’s the Dupe? by English playwright Hannah (Parkhouse) Cowley (“From a Correspondent” 46). The performance was met with high praise in the Saint John Gazette and Weekly Advertiser where a “Correspondent” wrote, “[the] scenes, decorations, and dresses were entirely new and in a very fine style.” The writer also added that “[some] of the Company displayed comic talents which would have done honor to a British Theatre and ‘tis justice to say that all exceeded expectations of the most favourable of their friends” (46). The performance was advertised as being put on “for Public Charity” at the price of three shillings with tickets to be bought throughout the day to prevent crowding at the doors when they opened at 5:30 pm for the 6:30 performance (Harper 260; Smith, Too Soon 4).

The amateur Company, who would call themselves the Loyalist Gentlemen Amateurs in later seasons, were dealing with limited space and a makeshift theatre (Smith, Too Soon 3). Advertisements for subsequent performances held in Mallard’s Tavern warned ladies against wearing tall hairstyles since raised seating was very limited by the room’s low ceilings (Smith, Maritime Stage 1-2). Nonetheless, the exhibition was so successful that a subsequent performance was advertised in the 27 March 1789 issue of the Saint John Gazette to take place on 2 April 1789. Early theatre critic Mary E. Smith states that “from the outset Saint John’s theatre-goers wanted to see themselves as part of a larger world” (Maritime Stage 7). Cultivating a vibrant theatre community with this first play enabled Saint John to establish its identity as a city in touch with the world. Smith says, “there remained a general attitude of superiority in Saint John – a feeling that Saint John was at least equal to any other city whether in Canada, Britain, or the United States” (Too Soon xi).

The Busy Body is a comedy of errors focussing on two sets of aristocratic lovers who wish to marry against the demands and influences of the guardian figures in their lives. Sir George Airy aspires to a union with Miranda who pretends to be in love with Sir Francis Gripe, Miranda’s guardian who only wants to marry her for her money. Charles, Sir George’s friend and Sir Francis’s son, wishes to marry Isabinda, daughter to Sir Jealous who intends her for a Spanish merchant. The “busy body,” a man named Marplot, is a fool who “longs to know [everyone’s] secrets” (Centlivre, 1808 ed. 13). In his attempts to aid his friends in their endeavours, he causes more problems than he solves. The lovers endure cases of mistaken identity, hasty searches for hiding places, Marplot’s endless foibles, and, above all, the disapproval of parental or guardian figures before finally being united in a fulfilling ending befitting a comedy.

Notably, the women in this play possess great agency. Miranda sets out the terms of her meeting with Sir George (18-20) and Isabinda “[consults] [her] reason” when confronted with a problem (37). The women take active roles in their fates, considering possibilities and displaying thoughtfulness and awareness of their situations. Isabinda weighs whether “confinement and plenty is better than liberty and starving” (37) and Miranda refers to the “tyrant man” and the “rigid rules” put in place to control women (14). The discussion of the tyrant recurs when Sir George implores Miranda to “[shake] off this tyrant guardian’s yoke” (27). The themes of subversion displayed in the discussions of tyranny, captivity, sacrifices for freedom, and what may be the traces of the beginnings of feminism all pertain to the social and political context in which the play was performed in 1789 at Mallard’s Tavern. Susanna Centlivre (1669?–1723), the playwright, led an unusual and activist life herself, overcoming the deaths of her parents and several spouses, dressing as a man to briefly attend Cambridge, and making a living using her skill as an actress and writer of comedies (Centlivre 1768). That background enabled her to write something that, unbeknownst to her, would become pertinent to the Loyalist experience in the new province of New Brunswick.

Not only had the Loyalists fled or been exiled from America to what, in 1783, was Nova Scotia (a new state seen by many as lacking political order), but they had also experienced political uprisings in their new home against the stringent rule of their own elites (Bell 86). Centlivre’s play, then, may have represented for them an escape from the “tyrant guardian’s yoke” (27). If so, the “guardian” may have been interpreted, as it was for fellow New Brunswick Loyalist Jonathan Odell, as the thirteen republican colonies or the rebelling New York- and New Jersey-based Loyalists (Bell viii, 86) rather than the elite or the British monarchy since many of the players and audience members who praised the performance were members of this elite (Smith, Too Soon 1). Four years before the Mallard Long Room was “converted into a pretty theatre” (“Correspondent” 46), there were riots outside the building organized against the elites being selected for leadership positions (Bell 104-05). Rioters were incensed that elites were superseding “those who had actually settled in the St. John Valley” and endured hardships for years (Bell 86).

The family names of these “men [of] influence” who “had the good sense to do their politicking in London rather than the wilds of Nova Scotia” feature not only in critic David Bell’s discussion of the more fortunate Loyalists (86), but also in Smith’s list of those in attendance at The Busy Body’s first performance (Maritime Stage 3). Colonel Edward Winslow, for example, travelled through winter conditions from Fredericton to see the play; Ward Chipman attended; and the sons of Jonathan Sewell, Jonathan Jr. and Stephen, both acted in the production (Smith, Too Soon 3; Harper 263). The aristocratic friends and neighbours of the Loyalist Gentlemen players, then, were witnesses to the historic performance. Since much of the class-based violence had abated in Saint John by 1789, the play was likely both a display of “the desire of the colonists for a cultural life of the kind they had left behind in New England” (Smith, Too Soon 1) and also a celebration of a fulfilling end, of order being restored to the ruling class of the New England Loyalists (Bell 86). It is certain, however, that a play such as this was not without its political weight. As an early hotbed for political uprisings and class-based strife, Saint John was a place of clashes: “government men against those who had not been admitted to privilege, […] New Englanders against New Yorkers, patricians against plebeians” (MacNutt 61). That history and tension in Saint John would have informed the reception of The Busy Body, imbuing it with potentially polarizing political power as was common in the years following New Brunswick’s establishment as a province. Whatever the exact reason for the play’s success, it did provide the opportunity for leading men and women of the new province to witness a comic allegory of some of the strife their early years in New Brunswick had created.

Hannah Zamora and Jonathan Harrison, Spring 2017

St. Thomas University

Bibliography of Primary Sources

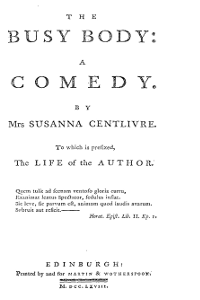

Centlivre, Susanna. The Busy Body: A Comedy by Mrs Susanna Centlivre to Which Is Prefixed, the Life of the Author. Edinburgh: Martin & Wotherspoon, 1768.

---. The Busy Body: A Comedy in Five Acts. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme […], 1808. Internet Archive. 8 February 2017

<https://archive.org/details/busybodyacomedy00centgoog>.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Bell, David. Early Loyalist Saint John: The Origin of New Brunswick Politics, 1783–1786. Fredericton, NB: New Ireland P, 1983.

Charlebois, Gaeton. “New Brunswick.” Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia. 16 Nov. 2015. Canadian Theatre. 8 Feb. 2017

<http://www.canadiantheatre.com/dict.pl?term=New Brunswick>.

“From a Correspondent” [Busy Body theatre review, prologue and advertisement]. The Saint John Gazette and Weekly Advertiser 27 Mar. 1789: 46.

Harper, J. Russell. “The Theatre in Saint John 1789–1817.” Dalhousie Review 34.3 (1954): 260-269.

Lawrence, Joseph W. Foot-Prints, Or, Incidents in Early History of New Brunswick. Saint John, NB: J. & A. McMillan, 1883.

MacNutt, W.S. New Brunswick, a History: 1784–1867. Toronto: Macmillan, 1963.

“Saint John New Brunswick: History-Time Date.” 12 Feb. 2017. New-Brunswick.net. New Brunswick Canada Tourism, Heritage and Culture.

<http://new-brunswick.net/Saint_John/timedate.html>.

Smith, Mary E. The Maritime Stage Number One: Saint John, 1789–1899. Saint John: U of New Brunswick, 1987.

---. Too Soon the Curtain Fell: A History of Theatre in Saint John, 1789–1900. Fredericton, NB: Brunswick P, 1981.